When someone suffers a serious injury or is diagnosed with a condition that threatens their arm or leg, one of the biggest questions they face is whether the limb can be saved—or if it should be removed.

Limb reconstruction tries to fix the injured part through surgeries, implants, and careful rehab. Amputation removes the damaged part and replaces it with a prosthetic. Both are life-changing. Both have risks. And both can offer a full, active life when handled with the right care.

But in some situations, amputation is not just the last resort—it’s actually the better option.

Understanding the Difference: What Makes Amputation and Reconstruction So Different?

What Limb Reconstruction Really Means

Limb reconstruction is a process that tries to save and repair an injured arm or leg. It can involve many things—surgery to fix bones, grafts to replace tissue, implants to support weak areas, or even devices like external fixators that hold bones in place while they heal.

This path is often chosen when doctors believe the limb can recover enough to be useful. The goal isn’t just to save the limb but to help it function again. That can mean restoring the ability to walk, grip, or move without major pain or risk of further damage.

The process can be long. Some people go through multiple surgeries over months or even years. Physical therapy plays a big role, helping to regain strength, movement, and control.

There are usually ups and downs, with periods of improvement followed by setbacks like infections, implant issues, or delayed healing.

Still, when it works well, reconstruction can help people keep their natural limb. That brings a deep sense of emotional comfort for many. It feels familiar. It feels like home. But the physical side doesn’t always match the emotional one.

Sometimes the saved limb is weak, stiff, or painful. It may need a brace to work. It may never return to full function. And for some, these trade-offs become too heavy over time.

What Makes Amputation a Stronger Choice in Some Cases?

Amputation is often seen as a last resort, but that’s not always the right way to think about it. In many cases, especially when the injury or illness is too severe, amputation offers a clearer path to recovery.

It removes the problem area and opens the door to a more stable, predictable life.

One of the main reasons doctors recommend amputation is when the chances of a useful recovery through reconstruction are low.

If nerves are destroyed, blood flow is poor, or infections keep returning, it may not be safe or realistic to keep the limb. In these situations, trying to save the limb could mean more pain, more surgeries, and more time away from normal life.

For some patients, amputation leads to a faster and more complete recovery. Once the wound heals and the person begins using a prosthetic, they often regain a high level of mobility and freedom.

Modern prosthetics are designed to move smoothly and support daily tasks—from walking and climbing stairs to driving and working.

There’s also a mental shift that happens after amputation. People often move from uncertainty to clarity. They know what to expect. They can build strength and skills around a stable solution, rather than waiting to see if a reconstruction will work.

That’s not to say amputation is easy. It requires emotional strength, physical rehab, and a good support system. But in the right cases, it gives people back control—and in some cases, more movement than they had with a failing limb.

When Doctors Start Considering Amputation

There are several moments when a doctor might start to recommend amputation over reconstruction. One of the most common is when a person’s injury includes serious damage to the nerves, blood vessels, and muscles.

If these can’t be repaired well enough to restore function, keeping the limb might offer little benefit.

Infections that don’t heal or that come back again and again are another reason. In some cases, infections spread to the bone or deep tissue, making it risky to try further surgeries.

Amputation removes the infected area and lowers the chances of the infection spreading through the body.

Severe trauma—like what happens in high-speed accidents or war injuries—can also lead to conditions where saving the limb is technically possible, but not practical.

If the recovery would take years, with many surgeries and a high chance of limited movement, doctors may explain that amputation could lead to better function and a quicker return to normal life.

Cancer is another situation where amputation can be the better choice. Some bone or soft tissue cancers grow in places where removing just the tumor is risky or could damage important structures.

In these cases, removing the limb may offer the best chance of survival and long-term health.

Sometimes, amputation is recommended after failed reconstructions. If earlier surgeries didn’t go well, or the limb remains painful and unstable, the person may reach a point where they no longer want to keep trying to save it.

In those cases, the choice to amputate comes from a place of clarity and self-care—not defeat.

What Patients Often Learn Along the Way

Many people who go through reconstruction start with a strong desire to save their limb. And that’s completely natural. It’s human to want to keep what you were born with. But after months of surgeries, setbacks, or pain, some people begin to see things differently.

What they learn is that saving a limb isn’t always the same as saving mobility. If the leg or arm is there but doesn’t work, it may not offer the freedom they hoped for.

That’s when people begin asking new questions—what kind of life do I want? What will let me move freely, work, travel, or take care of myself without help?

For people who choose amputation, many describe a shift in mindset. They move from hoping the limb will work again to learning how to live with a prosthetic that does work. And that change often brings confidence, independence, and relief.

It’s not the right answer for everyone. But in many real-life cases, especially when healing doesn’t go as planned, amputation turns out to be the better choice—not because something was lost, but because something better was made possible.

Long-Term Mobility and Quality of Life: What Really Matters

Looking Beyond the First Year

When someone faces the decision between amputation and reconstruction, it’s easy to focus on the short term. Most people ask, “How long will I be in the hospital?” or “How soon can I get back to work?”

But it’s just as important—if not more—to think about how your body will feel and function five, ten, or twenty years from now.

In the case of limb reconstruction, some patients do regain solid function. They return to work, walk without major pain, and live full lives. But for many, the reality is more mixed. Movement might stay limited.

The limb may always feel weaker or stiffer than before. There may be daily discomfort, swelling after activity, or the need for special shoes, braces, or walking aids.

That’s not failure—it’s simply a trade-off. Reconstruction gives you your own limb, but it may come with conditions. The challenge is that it’s hard to predict who will do well and who will struggle. Even with excellent surgeons and therapy, healing isn’t always a straight line.

Amputation, in contrast, offers a different kind of result. It removes the uncertainty of recovery and replaces it with a clear path forward. Once the site is healed and a good prosthetic is fitted, many people reach a consistent level of movement and independence.

That predictability matters more than people think. It allows you to plan your day without wondering whether your leg will hold up or if you’ll need help getting around.

It gives you confidence to travel, walk long distances, or take on physical work again—especially when your prosthetic is properly adjusted and you’ve had time to build strength and skill using it.

How Daily Life Feels Over Time

Mobility isn’t just about walking or using your hands. It’s about how your body feels during daily life. Are you able to move comfortably from room to room? Can you go to the market on your own? Can you sit, stand, carry bags, play with your kids, or take a walk without thinking too much about pain or balance?

People who choose reconstruction sometimes describe a lingering awareness of their limb—it’s there, but it doesn’t feel the same. It might ache on cold mornings.

It might limit how far they can walk. Certain movements might always feel unstable. These things add up. Over time, that awareness can feel heavy.

People with amputations describe their awareness differently. At first, everything feels new and uncertain. Learning to use a prosthetic is a full-time job at first.

But once it becomes second nature, they often stop thinking about it. They get up, put it on, and go. It becomes part of their routine, not something that holds them back.

This change in mental load—how much you have to think about your movement—is one of the key reasons many people find amputation leads to a better quality of life, especially when limb salvage would have left them with ongoing issues.

Emotional Recovery Is Part of Mobility, Too

How you feel inside plays a huge role in how you move through the world. People who feel confident and at peace with their bodies tend to stay active. They go out more. They keep doing the things they enjoy. And they recover faster—physically and emotionally.

Limb reconstruction can offer a strong emotional advantage in the early stages. It feels reassuring to know you still have your leg or arm. You don’t have to face questions or stares.

But if the limb doesn’t improve the way you hoped, that early emotional boost can fade, replaced by frustration, disappointment, or grief.

Amputation, on the other hand, often starts as a difficult emotional experience. There may be shock, sadness, or fear. But for many people, this period doesn’t last.

With time, support, and success using their prosthetic, they find a new kind of pride and strength. It’s not about looking “normal.” It’s about feeling capable again.

Neither path is emotionally easy, but both are survivable. The difference is in what kind of emotional toll you’re willing—and able—to carry in the long run.

Independence and Self-Reliance

One of the most important outcomes after any major surgery is independence. That means being able to care for yourself, move where you want, and live without needing constant help.

Limb salvage may let you do that if your recovery goes well. But if the limb stays weak or unstable, you may find yourself needing crutches, braces, or someone to assist you more often than you’d like.

With amputation, once the prosthetic is fitted and you’ve adapted to it, most people return to a high level of self-reliance. They dress, bathe, cook, drive, and work independently.

That sense of freedom can be a powerful factor in feeling truly healed—not just physically, but in life as a whole.

How Technology Is Changing the Game in Recovery and Mobility

Advancements in Prosthetic Technology

In the past, amputation often meant giving up certain activities or settling for limited movement. That’s no longer true. Today’s prosthetics are more advanced, comfortable, and adaptable than ever before.

These are not just tools for movement—they’re extensions of the body, carefully designed to help users live freely and naturally.

Modern prosthetic legs now include microprocessors that read the way you move and respond in real-time. These systems can automatically adjust to how fast you walk, help you handle stairs and slopes, and improve balance.

That means smoother movement and less effort, especially when walking for long periods or across uneven surfaces.

Some prosthetic feet have shock-absorbing or energy-return features. They store energy while walking and release it during your step, giving a spring-like push that makes each step easier. This not only reduces fatigue but also helps protect your joints over time.

For upper limb amputees, advanced myoelectric hands are now able to grip, pinch, and hold objects of different shapes and sizes. Sensors read muscle signals from the remaining limb and turn them into movements.

This allows users to do everything from holding a cup to typing or using a phone. While there is a learning curve, users who train consistently often adapt quickly and regain a wide range of motion and function.

These technological improvements mean that amputation no longer has to mean less mobility. In fact, for many people—especially those whose reconstructed limb doesn’t perform well—switching to a high-quality prosthetic can actually improve how much they’re able to do in everyday life.

Tools That Support Limb Reconstruction Recovery

Technology is also helping people who choose limb reconstruction. While prosthetics grab headlines, the tools used to support healing and function in saved limbs have come a long way too.

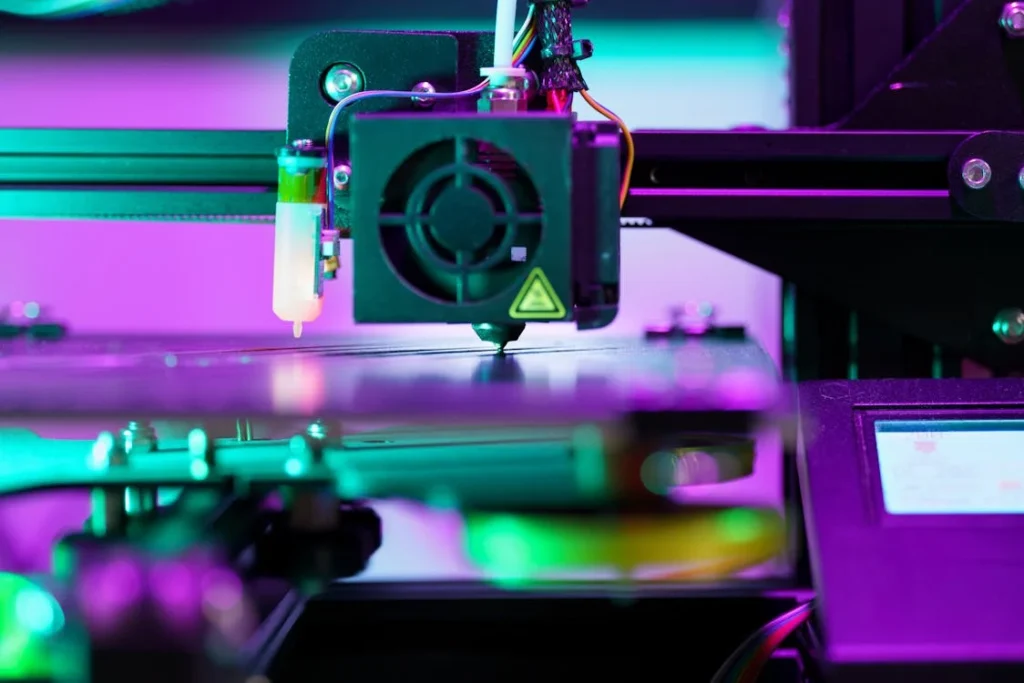

For bone injuries, custom 3D-printed implants and surgical plates are now used to rebuild or replace damaged sections.

These can be tailored to a person’s exact anatomy, improving how well the body accepts and adapts to the implant. They often speed up recovery and reduce complications.

External fixators, which hold bones in place from outside the body, are now more lightweight and better designed to allow movement during healing. This means patients can start rehab earlier, which is key to regaining strength and function.

In cases where nerves or muscles need to be reconnected, newer surgical techniques and biological therapies have helped improve the success rate.

These tools give doctors more options to preserve motion and sensitivity in the limb, although they often still require a long rehabilitation process to train the body how to use the limb again.

Robotic braces and wearable exoskeletons are also being introduced into rehab. These devices can assist with walking or limb movement, especially when muscle strength is limited.

They help patients practice proper motion, balance, and endurance in a safer way—making it easier to transition from assisted movement to independent control.

Virtual Rehab and Digital Therapy Support

One of the biggest breakthroughs in recent years is the rise of digital rehabilitation tools. Whether you’ve had an amputation or are recovering from limb reconstruction, staying motivated during rehab is often the hardest part. That’s where tech can make a big difference.

Gamified rehab programs use virtual tasks, interactive exercises, and real-time feedback to keep therapy interesting. Instead of repeating the same exercises in a clinic, patients can now do guided sessions at home that track progress, offer encouragement, and make it easier to stay consistent.

For amputees, motion sensors built into the prosthetic or wearable devices can help analyze walking patterns and detect small issues—like uneven weight shifts or incorrect step timing—that can lead to discomfort or injury if not corrected.

These sensors connect to apps that help adjust the prosthetic and offer tips for better alignment or pressure distribution.

Video consultations with therapists are also growing. These allow patients to stay in touch with experts no matter where they live.

Especially in areas where access to prosthetic care or physical therapy is limited, this kind of remote support helps bridge the gap and ensures that no one is left behind during recovery.

Technology Doesn’t Replace Effort—It Supports It

While these tools are impressive, it’s important to remember they don’t replace hard work.

Whether you’ve had a limb reconstructed or amputated, success still comes down to how engaged you are in rehab, how well your care is managed, and how willing you are to learn new ways of moving.

Technology is there to help make the path smoother—but it doesn’t walk it for you.

People who get the best results are those who use these tools as part of a bigger plan: one that includes physical therapy, emotional support, and a commitment to staying active and involved in their recovery.

If anything, the message is encouraging. We’re living in a time where you don’t have to settle for less—whether you keep your limb or move forward with a prosthetic, modern tools are there to help you live fully and move with confidence.

Talking to Your Care Team: Questions That Help You Decide

Why the Right Questions Matter

When you’re facing a decision as personal and life-changing as whether to amputate or try reconstruction, the people around you matter more than ever—especially your doctors. These are the people who understand your medical condition in detail.

They’ve seen what works, what doesn’t, and what recovery really looks like from both sides. But it’s up to you to ask the right questions, share your goals, and make sure you’re being heard.

Too often, patients sit in silence, unsure of what to say or ask. Or they nod along, even if they don’t fully understand the options. That’s natural—it’s hard to think clearly when emotions are high.

But this is your life, your body, and your decision. It’s worth slowing down, speaking up, and asking everything that’s on your mind, no matter how small or uncomfortable it feels.

The right questions won’t just help you understand the surgery. They’ll help you picture what your life will look like afterward. That’s where real clarity comes from—not from numbers or charts, but from imagining your future and asking if each option supports that vision.

Conversations That Go Deeper Than “Will I Walk Again?”

The most common question patients ask is, “Will I walk again?” or “Will I use my hand again?” It’s a good question, but it’s just the start. There’s a deeper layer beneath it—what kind of walking? How far? With how much pain? Using what kind of support?

Your care team should be able to tell you not just if you’ll recover, but how that recovery is likely to look. They can talk about timeframes, the number of surgeries, the need for braces or devices, and the chances of complications like infection or chronic pain.

These details are important. They shape how you plan your life, your work, and your healing.

Ask about outcomes not just in months—but in years. Ask how many people in your condition go back to work, resume driving, or return to their hobbies after each type of surgery.

Ask how often people in your situation end up switching from limb salvage to amputation later on. These answers will help you weigh the risk of investing time and energy into a process that may not give the result you want.

And don’t be afraid to ask your doctors for their honest opinion. They can’t—and shouldn’t—make the choice for you. But their experience matters. If they’ve seen ten cases like yours and eight patients had better lives after amputation, that’s information worth knowing.

Telling Your Doctors What Matters to You

Doctors are trained to look at the medical facts. They’re thinking about bones, blood flow, nerve function, and infection risk. But they don’t always know what your daily life looks like, or what kind of life you want to return to. That’s where your voice is essential.

Tell your care team what matters most to you. Is it walking long distances? Going back to a physical job? Being able to play sports, hike, or travel? Or is your emotional connection to your limb strong enough that you’d rather accept some physical limits in order to keep it?

Your values help shape the best plan. If your priority is speed and stability, your doctors might lean more toward amputation. If you’re more emotionally attached to your limb and are willing to go through a longer recovery, they might explore more reconstruction options.

Don’t hold back. The clearer you are about your lifestyle, goals, fears, and hopes, the better your care team can help you plan a path that works—not just medically, but personally.

Getting a Second Opinion Isn’t Just Okay—It’s Smart

Sometimes the best thing you can do is talk to more than one specialist. A trauma surgeon might see things differently than a cancer specialist.

A reconstructive surgeon may be focused on saving tissue, while a prosthetist can tell you what life looks like with a modern artificial limb.

Getting a second or third opinion doesn’t mean you don’t trust your doctor. It means you’re taking the decision seriously enough to make sure it’s well-informed. It also gives you peace of mind, knowing that whatever choice you make, you explored all sides before moving forward.

If you can, ask to speak with a physical therapist or a rehabilitation doctor too. These professionals often see the long-term effects that surgeons don’t always follow.

They can tell you how patients really do six months, one year, or three years later—not just how they are when they leave the hospital.

Some care teams may even connect you with former patients who’ve been through the same decision. Talking to someone who’s lived it—who knows what mornings feel like, what therapy is really like, what the emotional rollercoaster feels like—can give you clarity that no medical report ever could.

Making the Decision Together

The decision between amputation and reconstruction is yours. But that doesn’t mean you have to make it alone. Use your care team not just for treatment, but for partnership. Ask the hard questions. Listen closely. Speak openly.

This isn’t just a medical moment—it’s a turning point in your life. When everyone at the table is honest, thoughtful, and clear about what matters most, the decision becomes less overwhelming and more empowering.

The Financial Side of the Decision: What It Really Costs to Keep or Lose a Limb

Surgery Is Just the Beginning

One of the most misunderstood parts of deciding between limb reconstruction and amputation is cost. People often think about the initial surgery but forget the long-term financial and practical impact of each option.

But the truth is, this decision isn’t just about medicine or mobility—it affects your wallet, your job, your insurance, and your day-to-day expenses.

Reconstruction surgeries are usually more expensive up front. They often require multiple operations over a period of time. Each surgery comes with hospital stays, medications, imaging, lab tests, and follow-up visits.

You’ll also need a long stretch of physical therapy, often with specialized therapists who charge more per session.

Because the process is longer and less predictable, the costs can stack up in unexpected ways. For example, if a surgery doesn’t go as planned, or if you get an infection and need additional treatment, that adds more time, more hospital days, and more bills.

Even if you’re insured, these costs may not be fully covered, especially if you’re visiting private hospitals or need extra services.

It’s also important to think about how much time you’ll be away from work. A longer recovery can mean months—or even years—of reduced income, especially for people in physically demanding jobs.

That has ripple effects: missed payments, delayed family plans, or difficulty affording daily essentials.

The Real Cost of Amputation

Amputation also comes with serious costs, especially at first. There’s the surgery, the hospital stay, and wound care. Then comes the prosthetic, which is often expensive.

High-quality prosthetic limbs designed for comfort and long-term use are an investment—and they’re not one-time expenses.

Prosthetics wear out. On average, a prosthetic limb lasts 3 to 5 years before it needs replacement or repair. Your body may change shape over time, and that affects the socket fit.

Each adjustment or refitting comes at a cost. Some insurance plans cover part of this, but not all. Many require you to pay upfront and get reimbursed later, which can be tough if you’re already stretched thin.

That said, amputation often offers a shorter and clearer recovery path. Once you’re healed and fitted with the right prosthetic, you may be able to return to work sooner, regain independence faster, and reduce the need for ongoing surgeries and hospital visits.

Over time, that predictability may lower total costs—both financially and emotionally.

Amputation also tends to come with fewer missed workdays after the initial recovery. That’s a big deal for people who depend on their income to support a household, pay off loans, or manage other medical conditions.

Daily Life Costs Add Up

Whichever path you choose, life after surgery comes with new expenses. If you choose reconstruction, you may need mobility aids, special footwear, braces, or joint supports. These items wear down, need replacing, or require upgrading as your condition changes.

If you choose amputation, you’ll need to learn how to care for the residual limb, clean and maintain the prosthetic, and possibly adapt your living space—especially early in recovery.

Things like installing railings in the bathroom, getting a wheelchair temporarily, or modifying your vehicle for better access can add to the financial picture.

You may also need to travel often for physical therapy or follow-ups. In many parts of India, prosthetic and limb reconstruction services are available only in bigger cities, so transport, accommodation, and time off work can all become part of your cost structure.

These aren’t deal-breakers, but they’re important to understand early. The last thing anyone needs during recovery is the added stress of surprise expenses or delayed reimbursements.

Planning ahead helps reduce stress, gives you better control, and helps you make decisions that suit your long-term reality—not just what looks good on paper today.

Government Support, Insurance, and Local Access

In India, the financial side of this decision also depends on where you live and what kind of support is available.

Some states offer public hospital programs that reduce the cost of limb reconstruction, especially in trauma cases. Others may provide free or low-cost prosthetics through CSR initiatives, NGOs, or government schemes.

But access to these programs is uneven. It helps to speak with hospital social workers or case managers early in your care process. They can help guide you through what’s covered, where you can apply for aid, and how to access prosthetic care closer to home.

Insurance is another big factor. If you have coverage, make sure to review it in detail. Some policies have strict caps on rehabilitation or limit the number of prosthetic replacements they will cover.

Others don’t fully reimburse for private hospital care, which can catch families off guard.

If you’re not insured, understanding the full cost—from the first surgery to long-term rehab—is critical. Ask your care team to give you a full breakdown, not just of the surgery, but also of therapy, follow-up care, and any assistive devices you’ll likely need.

Making your decision with a full view of the financial impact isn’t just smart—it’s empowering. It ensures you’re not just choosing the right medical option, but the one that works for your life, your budget, and your future.

Cultural Perceptions and Social Identity: How Society Shapes the Decision

What the Limb Means in Our Minds and Communities

In many cultures, including in India, the body is more than just a physical shell. It’s tied closely to self-image, family roles, and how others see us.

When a limb is damaged or lost, the emotional impact often goes beyond the individual—it ripples into relationships, community interactions, and even how people feel about their place in society.

For some, keeping the limb—even if it isn’t fully functional—feels essential to their sense of wholeness. There’s a strong emotional connection to the idea of being physically complete.

In these cases, limb reconstruction may feel like the “more acceptable” or “less visible” option, especially in communities where disability is still misunderstood or where physical difference draws attention in public.

This pressure can affect decisions. Some people feel they must try to save their limb, even if the outcome is uncertain or the process painful, because they worry about what others will say or think if they have an amputation.

Sadly, this mindset sometimes leads people to continue down a treatment path that no longer makes sense medically—simply to meet social expectations.

Others may fear being seen as “less capable” if they lose a limb, even though prosthetic users today can do almost everything able-bodied people do, and often with more ease than someone struggling with a salvaged but nonfunctional limb.

Stigma, Shame, and Strength

Despite growing awareness, there’s still stigma around limb loss in many places. People may face unwanted pity, insensitive questions, or even discrimination at work.

This can make the idea of amputation feel heavy, not just because of the surgery itself, but because of what it seems to represent in society—a visible sign that something was lost or went wrong.

This is why emotional support, peer connection, and public education are just as important as medical treatment. People who meet others who’ve had amputations and are thriving often feel a sense of relief.

It helps reframe the conversation from one of loss to one of strength, choice, and empowerment.

Reclaiming identity after amputation doesn’t always happen overnight, but it often brings deep transformation. Many amputees speak of developing stronger self-confidence, clearer purpose, and new ways of connecting with others—not despite the amputation, but because of the resilience they built during recovery.

It’s also important to recognize how disability is viewed through different lenses. In some families, disability is something to be hidden or softened. In others, it’s a source of pride and perseverance.

How your family and friends respond can shape how you feel during recovery. This is why involving loved ones early—educating them, listening to their concerns, and sharing your own—can help prevent misunderstandings and emotional distance.

Challenging What Society Expects

When people understand that a prosthetic can provide better movement, faster recovery, and long-term independence, many shift their thinking. The fear of what others might say starts to fade when they see how capable and self-reliant they can become.

That shift doesn’t just help the person—it starts to change how communities view limb difference. Every person who walks confidently into a workplace, travels, plays sports, or speaks openly about their choice helps normalize prosthetic use and fight stigma at the root.

We’re seeing this change happen in real time across India and around the world. Athletes, teachers, entrepreneurs, and public speakers with prosthetics are showing that ability doesn’t depend on having all your limbs—it depends on having the tools and mindset to move forward.

As a result, the idea of amputation is slowly shifting—from something tragic to something transformative.

Choosing for Yourself, Not for Others

One of the hardest parts of making this decision is letting go of outside opinions. Family, friends, neighbors—even strangers—might have strong ideas about what you should do.

Some may push for saving the limb at all costs. Others might see amputation as giving up. And a few may simply not understand the full picture at all.

This is why it’s important to make the decision based on your values, your goals, and your quality of life—not someone else’s comfort. Your body, your energy, and your future belong to you.

Whether you choose to reconstruct or amputate, you have the right to make that choice with dignity and confidence. And no matter what anyone else believes, you are not defined by what’s lost—but by how you choose to move forward.

Conclusion

Choosing between amputation and limb reconstruction is not just a medical decision—it’s a deeply personal one. It affects your mobility, your future, your finances, and your sense of self. While limb reconstruction may seem like the natural choice, it’s not always the one that leads to the best quality of life. In many cases, especially when the damage is severe or healing is uncertain, amputation can offer a faster, more reliable path to independence.

Thanks to advances in prosthetics and rehabilitation, amputation is no longer a symbol of loss—it can be a gateway to renewed movement, stability, and strength.

The most important thing is to make a decision that aligns with your goals, your lifestyle, and your values—not someone else’s expectations. Talk openly with your doctors, ask tough questions, and take your time. Whether you choose to save the limb or move forward without it, what matters most is that the path leads you toward a life you feel confident and comfortable living.

You don’t have to walk it alone—and you don’t have to settle.