After a traumatic amputation, everything changes—how you move, how you feel, and how you get through your day. It’s not just the body that feels the shock. The mind does too. The road to recovery can feel long and uncertain.

But one thing that brings strength back—physically and emotionally—is physical therapy.

Physical therapy is not just about exercises. It’s about rebuilding control, confidence, and balance. It helps the body heal in the right way. It trains muscles to support new movements. And it prepares people to use their prosthetic limb with skill and safety.

The First Steps: Starting Therapy Early After Trauma

After a traumatic amputation, the body goes into a protective mode. There’s pain, swelling, and sometimes infection. Muscles go unused. Joints stiffen. Emotions run high. In these first days and weeks, it might feel like recovery is still far away.

But this is exactly when physical therapy starts to matter.

Many people think therapy begins only after the wound heals or the prosthetic is fitted. But the process starts much earlier—sometimes just days after surgery. The goal in the early phase isn’t to push the body, but to gently prepare it for what’s ahead.

Protecting Mobility Before It’s Lost

One of the biggest risks after amputation is losing mobility due to inactivity. When a person stays in bed for too long, the body begins to weaken.

Muscles shrink. Joints tighten. Circulation slows down. This can make later recovery more difficult and more painful.

That’s why physical therapists begin with simple movements—small stretches, gentle joint rotations, and breathing exercises.

These keep the blood flowing and help reduce swelling. Even just sitting up with support can improve posture and prevent stiffness.

These small actions might not seem like much at first, but they protect the body’s readiness for more complex movement later on. They also help maintain strength in the rest of the body, especially in the core, shoulders, and remaining limbs.

Therapists also teach patients how to move safely in bed, transfer to a wheelchair, or shift positions without putting stress on healing areas. These early lessons are about staying active without causing harm.

Learning to Work with the Body Again

Trauma affects more than just the injured limb. It changes how a person experiences their body. They might feel disconnected, unsure, or even afraid to move. Early physical therapy helps rebuild this connection.

Therapists take the time to explain what each movement does and why it matters. This helps the person feel more in control.

For example, they might guide a patient to tighten a muscle in the thigh or rotate the shoulder slightly—all while watching in a mirror. These simple exercises are not just physical. They are mental reminders that the body still works and can still learn.

This is also when therapists begin to shape the residual limb. Using soft wraps or shrinker socks, they gently guide the limb into a rounded shape that can support a prosthetic later.

If this step is skipped or done incorrectly, the limb may become swollen, uneven, or painful when trying to wear a socket in the future.

Therapists also check for early signs of issues like contractures—where a joint becomes locked in one position. If caught early, these can be treated with stretching and positioning. If left alone, they can limit movement for months.

Reducing Pain and Discomfort

Pain is a normal part of recovery, but it should not control the healing process. Physical therapy helps reduce certain types of pain by encouraging blood flow, teaching relaxation techniques, and reintroducing movement slowly.

One common issue is phantom limb pain—the feeling that the missing limb is still there, sometimes with burning or cramping. This can be frustrating and hard to understand.

But physical therapy has ways to help. Techniques like mirror therapy, massage, and guided movement can retrain the brain and calm the nervous system.

Therapists also teach breathing and visualization methods that help lower stress. When the body is relaxed, it heals better. These approaches help patients manage discomfort without always relying on heavy medication.

Some people also feel pain because they are unknowingly using muscles the wrong way. For example, someone who lost a leg might put too much strain on their back or shoulders when moving around.

Therapists can spot these patterns early and teach better ways to move, sit, or lift.

Emotional Support Through Movement

After amputation, emotions can shift quickly. Some days feel hopeful. Others feel heavy. Recovery is not just about what the body can do—it’s also about how the person feels doing it.

Therapists are often some of the first people patients open up to during recovery. Through regular sessions, a bond forms. The patient begins to trust that progress is possible.

They begin to set small goals—sit longer, stretch further, stand with help. Each achievement builds confidence.

Physical therapy also brings routine. In the chaos of hospital life or post-surgery healing, having a clear plan—even if it’s just a 20-minute session—creates structure. That structure helps people feel grounded.

In this way, therapy becomes more than just physical. It becomes a space where recovery feels real and active, not just something happening in the background. It helps shift the mindset from “I lost something” to “I am learning something new.”

Preparing for Prosthetic Use: Building Strength, Balance, and Trust

Once the initial healing period is over and the residual limb is stable, the focus of physical therapy begins to shift. Now, it’s about preparing the body for prosthetic fitting—and making sure the person is ready for the new kind of movement that’s coming next.

This isn’t just about building muscle. It’s about retraining the brain, restoring coordination, and helping the person feel confident enough to take the next step—literally.

Training the Muscles to Support a New Way of Moving

Every limb plays a role in balance and movement. When one is lost, the entire body has to adjust. Without physical therapy, these changes can feel clumsy and unsteady. But with the right training, the body can learn new patterns—and do so smoothly.

Therapists begin by strengthening the muscles that will be most active during prosthetic use. For leg amputees, this often means the hips, glutes, thighs, and core.

For arm amputees, it might be the shoulder, upper back, and abdominal area. These muscle groups help control posture and maintain balance.

Exercises may start in sitting or lying positions to build endurance. Then they move to standing, shifting weight from side to side, or stepping with assistance. Each step helps the body prepare for the pressure and movement of using a prosthetic limb.

The goal is not just to walk again. It’s to move safely—without overcompensating, without pain, and without fear of falling. That means careful attention to posture, alignment, and joint stability.

Practicing Movement Without the Prosthetic First

It may seem strange, but some of the most important training happens before a prosthetic is even worn. Therapists guide patients through “pre-prosthetic” exercises that mimic the movements they’ll need later—such as rising from a chair, balancing on one leg, or turning while walking.

This training allows the person to get used to shifting weight and coordinating movement. It also gives therapists a chance to spot imbalances or weaknesses that might make prosthetic use more difficult.

Practicing without the device first gives patients time to focus on their own body—how it feels, how it responds, and where it needs support. Then, when the prosthetic is added, the learning curve becomes smoother.

This also reduces frustration. If a person struggles to walk with a prosthetic but has never practiced weight shifting or core control, they may think the device is the problem.

But when they’ve already learned the basics, it becomes clear what to expect—and how to improve.

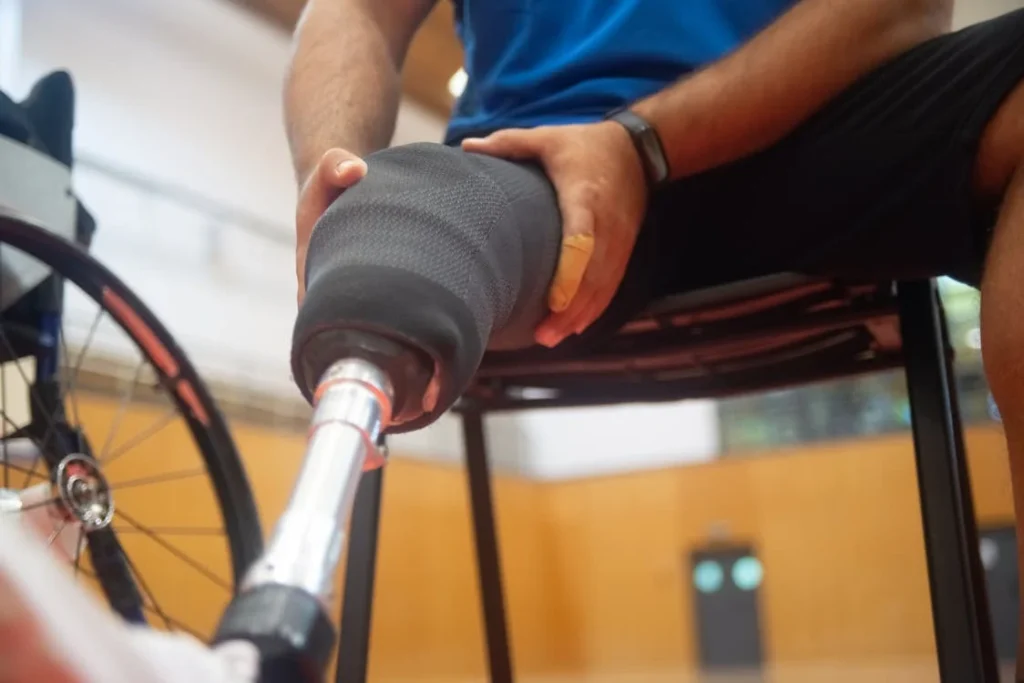

Helping the Limb Adjust to Pressure

A prosthetic socket must fit snugly over the residual limb. It carries weight, transfers motion, and keeps the device in place. But for someone recovering from trauma, the limb may still be sensitive.

The skin may be delicate. Scar tissue may be thick or uneven. This makes the transition into a prosthetic more complex.

Physical therapy helps the limb adapt to this pressure gradually. Therapists may use soft compression tools, massage, or specialized wrapping techniques to shape the limb and reduce swelling.

They also guide the patient through exercises that help the limb handle more weight over time.

If the patient rushes into prosthetic use without this preparation, they may develop skin breakdown, pain, or discomfort that causes them to avoid wearing the device altogether.

But when the limb is slowly conditioned, the body adjusts—and the prosthetic feels like a natural extension instead of a foreign object.

Therapists also help monitor fit and alignment during this time. If something feels wrong—pinching, slipping, or pressure on a sensitive area—they can alert the prosthetist for adjustments. This close attention prevents small problems from becoming big setbacks.

Building Balance and Preventing Falls

Falls are one of the biggest risks for new prosthetic users. Losing a limb affects the body’s natural balance system. Without careful training, people may lean too far forward, put too much weight on the remaining limb, or take uneven steps. These habits lead to poor posture and a higher chance of injury.

Therapists focus on restoring balance from the ground up. This may include simple exercises like standing on one foot, using a balance board, or walking between rails. These tasks challenge the body to stay upright and centered.

Over time, these exercises become more advanced—walking on uneven surfaces, turning quickly, or climbing stairs. The goal is to make real-world movement feel safer and more predictable.

For upper limb amputees, balance is affected in a different way. The loss of an arm changes the body’s center of gravity.

Physical therapy helps them regain coordination, especially for activities that involve both sides of the body—like dressing, lifting, or driving.

Therapists also teach how to fall safely and get up from the ground. These may seem like small things, but they give people confidence.

Knowing what to do if something goes wrong reduces fear—and helps the person stay active instead of avoiding movement.

Supporting Emotional Growth Through Physical Progress

This stage of recovery is often where people begin to feel real progress. They see their strength return. They move more smoothly. They begin to believe that life with a prosthetic is not only possible—but within reach.

Therapists encourage this growth by setting small, achievable goals. One day it might be standing longer. Another day, it’s walking a few extra steps. These wins are shared and celebrated, building momentum for the harder days ahead.

As the person prepares to receive and use their prosthetic, they are no longer starting from zero. They are strong, prepared, and already familiar with the movement patterns they’ll need.

This preparation—both physical and emotional—makes a huge difference. It reduces the time needed to adapt to the device. It increases the chances of consistent use. And it builds a sense of trust in the body again.

After the Prosthetic: Relearning Movement, One Step at a Time

Getting a prosthetic is an important moment in recovery. But it’s not the finish line—it’s the beginning of a new phase. The body has to adjust. The brain has to adapt. The person has to learn to move in a new way.

This is where physical therapy becomes more detailed, more practical, and more focused on everyday tasks. It’s no longer just about healing. It’s about living—on your feet, on the move, and on your own terms.

Learning to Walk Again

Walking with a prosthetic isn’t like walking with a natural limb. Even the most advanced devices require new movement patterns. Muscles fire differently.

The joints move in new directions. Balance must be controlled with more awareness. Every step, especially early on, takes concentration.

Physical therapists help break this process down into manageable steps. It starts with posture. Is the spine straight? Are the hips aligned? Is weight evenly distributed?

Then comes weight shifting and stepping. The therapist might guide the person to place the prosthetic foot forward, slowly transferring weight onto it.

This can feel strange at first—like stepping on something that isn’t truly part of the body. But with repetition, the movement begins to feel more natural.

Therapists often use parallel bars in the early stages. These give the person a safe space to practice walking without worrying about balance. Over time, they move to using canes or crutches. Eventually, many patients walk without support at all.

Each phase is paced to match the person’s comfort and progress. Rushing can lead to stumbles or reinforce bad habits. Going too slowly can reduce confidence. The therapist finds the right rhythm.

Walking practice also includes turning, side-stepping, climbing stairs, and managing uneven surfaces. These are real-world movements that patients will face daily. The more they practice in therapy, the less fearful they feel in public or at home.

Building Endurance and Energy Efficiency

Walking with a prosthetic often takes more energy than walking with two natural limbs—especially in above-knee amputations. The body works harder to keep balance and create momentum.

Physical therapy helps improve endurance. This includes strengthening the legs, core, and cardiovascular system. Over time, what feels exhausting at first becomes easier. The body becomes more efficient. Breathing evens out. Movements become smoother.

Therapists also teach strategies to conserve energy. For instance, they may adjust the person’s gait to reduce wasted motion. They might suggest using handrails or pacing daily activities to avoid fatigue.

This matters not just for walking, but for everything else—working, cooking, playing with children, even standing in a queue. Energy conservation allows people to do more with less strain.

Improving Functional Independence

Once basic movement is under control, physical therapy turns toward daily activities. The goal is simple: help the person live as independently as possible.

For lower limb amputees, this may include tasks like standing at the sink, transferring from a chair to a bed, or using the bathroom safely.

These movements seem small, but they require balance, coordination, and confidence—all of which are strengthened in therapy.

Therapists may set up simulations of real-life settings: a kitchen corner, a mock bathroom, or a desk. Practicing in these spaces prepares the patient for challenges at home or work.

For upper limb amputees, therapy focuses on grip control, reach, and fine motor coordination. This might involve holding utensils, opening doors, typing on a keyboard, or folding clothes.

Each movement is broken down, practiced, and adjusted to match the user’s device and needs.

Therapists also guide patients on how to adapt when things don’t go as planned—like how to pick something up off the floor, catch their balance after a misstep, or manage stairs with a heavy bag.

These practical skills restore confidence and reduce dependence. They also rebuild a sense of routine, which is deeply important for emotional well-being.

Managing Changes Over Time

As the person gets stronger and more active, their body continues to change. Muscles build. Limb shape may shift. The prosthetic might need adjustments.

Sometimes, pain can return, or a new goal may emerge—like running, cycling, or returning to work.

Physical therapy adapts to meet these needs. It’s not a one-time event. It’s an ongoing relationship between the therapist and the patient.

Therapists check for signs of poor posture, imbalance, or muscle tightness. They update the exercise plan. They coordinate with the prosthetist to ensure the device still fits properly.

They also watch for emotional signals—like frustration, burnout, or fear of movement—and respond with encouragement and strategies.

For many patients, therapy continues for months or even years, depending on their goals. Some come back periodically for tune-ups. Others join group sessions or community rehab programs to stay active.

The key is that physical therapy doesn’t end when the person walks again. It continues as long as needed—supporting each new step in the journey.

Empowering the Patient

Perhaps the most important part of physical therapy is empowerment. Every goal reached builds belief. Every challenge overcome reminds the person that they are still in charge of their body—and their life.

Therapists are more than instructors. They are coaches, cheerleaders, problem-solvers, and quiet supporters. They listen without judgment. They celebrate small wins. They offer solutions when things feel stuck.

Over time, patients begin to carry that voice with them. They stop thinking, “I can’t,” and start asking, “How can I?”

This shift in mindset is what transforms recovery into resilience. It’s what turns a prosthetic from a tool into a trusted part of daily life.

Tailoring Therapy to the Type of Amputation

No two amputations are exactly the same. A person who has lost a leg below the knee will face very different challenges compared to someone who has lost an arm above the elbow.

The level of amputation, the cause of trauma, and the person’s age, health, and lifestyle all shape the therapy journey.

That’s why physical therapy after traumatic amputation is never one-size-fits-all. It’s always personalized.

Therapists take time to understand each person’s injury, their body’s unique response to healing, and the kind of life they want to return to. From that point, they build a plan that’s realistic, focused, and flexible enough to grow with the patient’s progress.

Below-Knee and Above-Knee Amputations

For lower-limb amputations, the goal is to restore walking, standing, and balance as efficiently and safely as possible. With a below-knee amputation, the person still has their knee joint.

This gives them a big advantage in movement and control. Therapy in these cases focuses on strengthening the hips and thigh, maintaining ankle alignment on the sound side, and gradually introducing the prosthetic.

With above-knee amputations, the challenge increases. Without a natural knee, the body has to work harder to create a walking rhythm.

A prosthetic knee must be controlled either mechanically or electronically, and that requires more core and hip strength. Therapists work closely on weight distribution, stride control, and posture to avoid strain on the lower back or opposite leg.

Stair climbing, ramp walking, and quick turns are usually added later in therapy. These tasks mimic daily life and help prevent the patient from relying on just flat, predictable surfaces.

Therapists also prepare the patient for uneven terrain, slippery surfaces, and real-world settings. This helps reduce anxiety, increase independence, and lower the risk of falls in public spaces.

Upper Limb Amputations and Fine Motor Training

For people who have lost an arm or hand, therapy looks very different. The focus is on rebuilding reach, grip, hand-eye coordination, and body balance. Without an arm, even simple actions like opening a bottle or tying shoelaces require new techniques.

If a myoelectric prosthetic is used, therapy includes learning to activate and control sensors using muscle signals. This requires concentration and repetition, but over time, the brain adapts to the new way of moving.

Therapists also help the patient strengthen the remaining arm and shoulder, which now have to do more work. If the dominant hand was lost, therapy may include retraining the non-dominant hand to write, eat, or perform detailed tasks.

In both lower and upper limb cases, therapists help patients build practical routines—whether it’s getting dressed, using a phone, cooking, or driving. These routines are practiced repeatedly until they feel automatic and natural again.

Long-Term Adaptation and New Goals

One of the most powerful parts of physical therapy is that it grows with the patient. What starts as learning to stand may evolve into returning to work, hiking, or even competitive sports. The therapy plan shifts with each new phase.

As people return to daily life, new challenges often appear. They may feel pain after long walks, or notice the prosthetic feels heavy during certain tasks.

They may want to increase speed, stability, or range of motion. They may simply want to feel stronger.

Therapists address these challenges by adjusting exercises, introducing new techniques, or collaborating with prosthetists for device upgrades.

They continue checking body alignment, balance, and strength—ensuring the patient is always improving, not just maintaining.

For those who experience setbacks—like falls, socket pain, or secondary injuries—therapy provides a safe space to recover without losing momentum. The goal is always to keep the person moving forward, no matter how small the steps.

Managing Lifestyle Changes

Traumatic amputation affects more than the body—it affects relationships, jobs, hobbies, and mental health. Physical therapy often touches each of these areas by helping people reclaim control over how they live.

Therapists support return-to-work planning, especially for people in physically demanding roles. They simulate tasks, assess ergonomic needs, and prepare the person for the physical strain of specific jobs.

They also offer advice on home setup, helping patients and families make small changes—like adjusting furniture height or installing grab bars—to support safer movement.

Social confidence is another big factor. Many people worry about how they’ll be perceived with a prosthetic or fear stepping into public spaces.

Therapy helps build confidence by focusing on skills like carrying bags, using public transport, or joining social events. The stronger and more capable a person feels physically, the more willing they are to re-enter the world emotionally.

Therapists may even recommend support groups, peer mentoring, or recreational activities where individuals can connect with others who have gone through similar journeys.

Aging With a Prosthetic

Physical therapy also plays an important role as prosthetic users age. Over time, the body changes. Muscle mass may decrease. Joint pain may develop. The prosthetic itself may no longer fit as well.

Therapists help adjust exercise routines to match the body’s new needs. They focus more on flexibility, endurance, and joint protection. For older users, therapy can help prevent falls, reduce fatigue, and improve confidence in using mobility aids.

Even decades after an amputation, therapy remains a valuable tool. It’s not just about recovering from an injury—it’s about maintaining mobility for life.

Recovery at Home: The Power of Family and Everyday Movement

Once a patient leaves the hospital or rehab center, the real world sets in. The structured support of therapists, nurses, and specialists is replaced by familiar surroundings—and often, the support of family members.

While this transition is a milestone, it can also be overwhelming. That’s where home-based physical therapy and family engagement become powerful tools.

Healing continues long after a person returns home, and the way the home environment is managed can either speed up recovery or slow it down.

Physical therapy doesn’t end at the clinic door. In fact, the most meaningful progress often happens at home—where movement becomes part of daily life, not just a scheduled session.

Making the Home Recovery-Friendly

After a traumatic amputation, a person’s needs change. The home, which once felt easy to navigate, can suddenly present barriers—stairs, low seating, cluttered walkways, and slippery floors.

Physical therapists often help families adapt the home to support safer movement. This might include raising chairs for easier transfers, adding railings in the bathroom, improving lighting, or simply rearranging furniture to create space for walking practice.

These small changes have a big impact on confidence and safety.

A home that supports movement becomes a built-in training space. Every room becomes part of recovery. The hallway is a balance lane. The living room becomes a stretching zone. The kitchen becomes a place to practice standing endurance.

In India, multigenerational homes are common, and with support from family members, these spaces can be adapted in thoughtful, affordable ways.

Families may also share caregiving responsibilities, creating more opportunities to encourage exercise and mobility.

The Role of Caregivers in Daily Therapy

Family members often play the role of caregivers, especially in the months after discharge. But many don’t realize how influential they can be in physical recovery—not just by helping, but by empowering.

Therapists often train family members on basic techniques: how to assist safely during stretches, how to monitor posture during walking, how to apply wraps or don prosthetic socks, and how to spot signs of skin pressure or pain.

This involvement keeps the patient consistent with their exercises, even when motivation dips.

More importantly, it turns therapy into a shared effort, not a solitary struggle.

For example, a spouse may practice walking alongside their partner, matching pace and offering encouragement. A parent may help a child with grip-strength exercises during homework breaks.

A sibling might play balance games to build coordination in a fun, non-clinical way.

These moments of interaction not only improve physical outcomes—they also lift spirits. They turn movement into connection.

Bringing Therapy Into Routine

In-home recovery works best when therapy is integrated into daily habits. This doesn’t mean hours of structured exercise. It means turning regular activities into purposeful movement.

Therapists may suggest:

- Standing at the sink for brushing teeth to practice weight-bearing.

- Doing stretches while watching TV.

- Using steps at the entrance for safe stair practice.

- Practicing sit-to-stand during prayer times or before meals.

These small, repetitive tasks train muscles and teach the body new patterns. They also help prevent sedentary habits, which can lead to deconditioning or imbalance over time.

This is especially useful for people in rural areas or those who cannot travel easily to therapy centers. With basic tools and clear instruction, a home can become a recovery space that feels safe, familiar, and motivating.

The Emotional Impact of a Supportive Home

Recovery isn’t just physical. It’s emotional. And after traumatic amputation, the home is often where the emotional challenges appear most clearly.

A supportive home doesn’t just provide help—it offers dignity. It allows the person to feel in control again, to try things without judgment, and to move at their own pace. It also helps reduce anxiety, which can be a major barrier to physical progress.

Therapists who involve family members in planning and communication often see stronger outcomes. The patient doesn’t feel alone. The family doesn’t feel helpless. Everyone understands the goals—and works toward them together.

This kind of support is especially powerful in Indian households, where emotional connection and shared responsibility are deeply valued. When families become part of the therapy journey, progress becomes a shared victory.

Culture, Community, and Belief: The Unseen Forces Behind Recovery

When someone loses a limb due to trauma, the journey ahead isn’t just shaped by doctors, therapists, or devices. It’s also shaped by something more invisible, yet just as powerful—culture.

Beliefs about health, disability, strength, and dependence influence how a person responds to therapy, how they see their own body, and how they re-enter society.

In India, where cultural identity is often tied to community and family roles, these unseen forces can either support recovery—or quietly stand in its way.

The Influence of Cultural Beliefs

Across India, ideas about healing, mobility, and disability vary by region, religion, and tradition. In some communities, using a prosthetic may be seen as a sign of resilience.

In others, it may be met with hesitation or stigma. These beliefs affect how quickly people seek therapy, how consistently they follow through, and how openly they talk about their struggles.

For example, some people may feel that using a prosthetic means accepting “incompleteness,” and avoid wearing it outside the home.

Others may feel pressure to appear strong and avoid therapy altogether, believing that asking for help is a sign of weakness.

Therapists working in diverse cultural settings must be sensitive to these perspectives. They must build trust before pushing progress. They may need to involve spiritual leaders, elders, or respected voices in the community to help the patient feel supported in their recovery—not ashamed of it.

Cultural sensitivity also means understanding beliefs around pain. In some settings, people may tolerate extreme discomfort without reporting it, believing it’s part of the process.

Others may avoid movement altogether, fearing it will cause damage. Education, patience, and open conversation are critical here.

The Power of Language and Identity

How a person talks about their body matters. The words used in therapy, in families, and in the community all shape how someone feels about their healing.

Terms like “disabled,” “broken,” or “dependent” can create emotional barriers. They make the person feel less than who they were before. But when the focus shifts to “adaptation,” “strength,” and “growth,” recovery becomes about progress, not loss.

Therapists who use positive, empowering language—especially in the person’s native tongue—can break through mental blocks. They help the patient see themselves as strong, capable, and full of potential.

In India’s multilingual environment, translation matters. Therapy instructions that sound too clinical or foreign may not resonate. But when explained in a familiar way—with relatable examples and local references—they become easier to absorb and apply.

Community Attitudes and Social Reintegration

Physical therapy does more than train the body—it prepares people to return to their community. But if that community is not ready to accept them, the transition can be isolating.

Some people fear judgment in public places—on buses, in markets, at weddings. They may worry about how others will react to their limp, their prosthetic, or their changed appearance. These fears can make people withdraw socially, even if they’re doing well physically.

This is where community awareness becomes part of therapy. Support groups, disability rights organizations, and inclusive events all help normalize life with a prosthetic.

When the community sees people walking, working, and thriving after trauma, social attitudes begin to shift.

Some rehab centers now organize peer mentorship, where experienced prosthetic users meet with those just beginning their recovery.

These mentors offer lived experience, practical advice, and emotional encouragement. They also serve as role models within the community, changing how amputation is seen—not as an end, but as a new beginning.

Religious and Spiritual Support in Healing

For many Indians, faith plays a central role in health and recovery. After trauma, people often turn to spiritual practices for comfort, meaning, and strength. Temples, mosques, churches, and gurudwaras become places of peace and support.

Therapists who acknowledge and respect this connection help bridge the gap between physical and emotional healing. They may suggest gentle movement exercises during prayer routines, or encourage walking to places of worship as part of rehab.

When faith is included—not excluded—people feel whole. They feel seen not just as patients, but as human beings with beliefs, emotions, and purpose.

Conclusion

Recovery from a traumatic amputation is not a straight line. It’s a journey made up of small, meaningful steps—each one shaped by effort, support, and belief. Through every stage, physical therapy remains at the heart of that process.

From the moment the body begins to heal, therapy gives it structure. It builds strength, restores balance, and teaches the body to move in new ways. It transforms pain into progress and fear into confidence. But more than anything, it reminds people that they are not defined by what they’ve lost, but by what they’re still capable of doing.

Therapists, families, communities, and the patients themselves all play a role. Together, they create a system of support where each movement is a win, each day a little stronger than the last.

The goal of physical therapy isn’t just to walk or lift again. It’s to live—fully, freely, and without apology. And for every person who has faced a traumatic amputation, that goal is always within reach—with the right support, the right mindset, and the steady guidance that only physical therapy can provide.