Losing a limb is life-changing. But for many people, the pain doesn’t end there. Even after a limb is gone, the body and brain can still feel it. This strange and often painful feeling is called phantom limb pain. It’s real. It’s confusing. And for many, it’s deeply frustrating.

If you or someone you love is dealing with phantom pain after a traumatic injury, you are not alone. Many people face this silent struggle. It can affect sleep, mood, movement, and the way you live day to day. The pain may come and go. Sometimes it feels like burning. Sometimes it’s sharp, like a cramp or electric shock. And sometimes, it’s hard to even explain.

But here’s the good news: it can be managed. There are real steps you can take to reduce the pain. You don’t have to just live with it.

Understanding Phantom Limb Pain After Trauma

Phantom limb pain is one of the most unusual and frustrating things a person can experience after losing a limb. The pain feels real, because it is real—even though the limb is no longer there. It isn’t in your head.

It’s your brain and nervous system trying to make sense of a sudden loss. To understand how to manage it, it’s important to first understand where it comes from and what it feels like.

What Exactly Is Phantom Limb Pain?

Phantom limb pain is the feeling of pain in a part of the body that no longer exists. After a leg or arm is amputated, the nerves in the body still send signals to the brain.

The brain, which was used to getting signals from that limb, continues to “expect” input from it. When those signals stop or become confused, the brain can misinterpret this as pain.

This isn’t just a memory or emotional reaction. It’s a physical response. It’s caused by changes in the way the brain, spinal cord, and nerves talk to each other. The brain creates a kind of “map” of your body. After an amputation, that map doesn’t update instantly.

So, even though the limb is gone, the brain keeps acting like it’s still there. That’s why you might still feel itching, pressure, tingling—or pain—in a part that’s no longer there.

Sometimes, this pain starts right after surgery. Other times, it may not begin until weeks or months later. It can be mild and annoying, or it can be intense and constant. Either way, it can interfere with daily life in a big way.

Why Does It Happen After Trauma?

When a limb is lost because of a sudden injury—like an accident, explosion, or severe damage—the nerves in that area are shocked. They don’t get time to slowly shut down or heal. Instead, they’re suddenly cut off, and they respond by sending out loud, confused signals.

The brain, already under stress from the trauma, tries to make sense of those signals. But because the limb is no longer there, it interprets those signals as pain.

This is different from losing a limb through planned surgery, where the body and brain might have a little more time to adjust.

Also, trauma often comes with emotional stress—shock, fear, grief, and even guilt. These strong feelings can make pain feel worse. The brain doesn’t work in separate boxes for emotions and pain.

They influence each other. So trauma increases the chance that phantom limb pain will appear and stick around.

What Does Phantom Limb Pain Feel Like?

Phantom limb pain doesn’t feel the same for everyone. That’s part of what makes it so hard to treat. You might describe it as burning, stabbing, throbbing, or even like electric shocks.

Some people say it feels like the missing limb is being squeezed, twisted, or bent into an unnatural shape.

At times, the pain might be steady. At other times, it might come in sudden waves. It can wake you up at night. It can stop you from using a prosthetic or getting around.

And the strangest part is that you might feel all of this in a part of your body that’s no longer there.

Some people also feel phantom sensations that aren’t painful. You might feel like your hand is still there, or that your foot is still moving. These are common, too. But when these sensations turn painful, that’s when they become a serious problem.

Is It the Same for Everyone?

Not at all. Phantom limb pain is different from person to person. Some people never get it. Others feel it often. Some only feel it when they’re tired or stressed. Others may feel it during certain weather changes or emotional situations.

What makes it even more complex is that it doesn’t always follow the same pattern. You might go weeks without any pain, and then have a flare-up.

Or it might start suddenly months after your injury. Some people feel pain in one part of the missing limb. Others feel it throughout the whole area.

It can also change over time. For example, it might start as a sharp, stabbing pain and later turn into a dull ache. These shifting patterns can make it hard to explain or predict. But learning your own pain pattern can be the first step in taking control of it.

What Happens in the Brain?

When a limb is lost, the part of the brain that controlled it doesn’t shut off. Instead, it waits for signals that no longer come. Over time, that area of the brain may start to “borrow” signals from nearby areas.

For example, the part of the brain that controlled your missing hand might begin responding to signals from your face or upper arm. This change is called “cortical reorganization.”

Sometimes, this reorganization helps reduce pain. But other times, it adds to the confusion. The brain may misfire or create false sensations.

This is why treatments that help the brain “relearn” its new shape—like mirror therapy or virtual reality—can actually help reduce phantom pain.

There’s a lot we still don’t fully understand. But what we do know is that phantom pain is not imaginary, and it is not your fault. It’s your body’s way of trying to cope with a sudden and difficult change.

How to Manage Phantom Limb Pain Effectively

Living with phantom limb pain can be exhausting. It affects your sleep, your mood, your focus, and sometimes even your relationships. But you don’t have to suffer in silence.

While there’s no single cure, there are many ways to reduce the pain, retrain the brain, and feel more in control again. The best part? You don’t need to do it all at once. You can start small, one step at a time.

Finding the Right Treatment Mix

There’s no one-size-fits-all solution for phantom limb pain. What works for one person may not work for another. That’s why doctors often recommend a mix of treatments.

Sometimes it takes time to figure out what combination works best for you. Patience is key, and so is being open to trying new things.

Some treatments focus on the body. Others work on the brain. And some help with both at the same time. Let’s go over the main types of approaches you can try.

Mirror Therapy: Training the Brain with Reflections

One of the simplest but most powerful tools is mirror therapy. This involves placing a mirror next to your remaining limb in a way that makes it look like the lost limb is still there.

When you move your existing limb and watch its reflection, your brain gets visual feedback that tricks it into thinking the missing limb is moving too.

Over time, this can help reduce the confusion in the brain and ease the pain. For many people, this technique is surprisingly effective. It’s safe, drug-free, and can be done at home.

All you need is a mirror and a quiet space to practice. You won’t see results overnight, but with daily use, many people report that the pain starts to fade.

Desensitization Techniques: Calming the Nerves

After trauma or amputation, the nerve endings around the residual limb can become overactive and super sensitive. These nerves may send pain signals even when they shouldn’t. Desensitization is a way to gently calm those nerves down over time.

This usually starts with gently touching or rubbing the end of your limb with different textures—like soft cloth, sponge, or cotton balls. Over time, your skin and nerves get used to being touched again.

You can also try tapping, massaging, or using vibration to stimulate the area. The goal is to reintroduce touch slowly, in a controlled way, so your body doesn’t react with pain.

Doing this every day can help quiet the nervous system and reduce phantom sensations. It’s especially helpful when combined with other therapies.

Medications: What Can Help and What to Watch For

Painkillers like paracetamol or anti-inflammatory drugs may help a little with phantom pain, but they often don’t do enough on their own.

That’s because this kind of pain isn’t just coming from the body—it’s coming from the brain’s response to nerve signals. That’s why doctors sometimes prescribe medicines that work on the nervous system.

These may include certain antidepressants or anti-seizure drugs—not because you’re depressed or having seizures, but because these medicines can calm nerve signals in the brain and spinal cord.

Drugs like amitriptyline or gabapentin are commonly used. They can help reduce the intensity and frequency of phantom pain.

Some people find relief with patches or creams that numb the area around the amputation. In some cases, doctors may suggest pain-blocking injections, especially if the pain is severe and constant.

It’s important to work closely with a doctor who understands phantom pain. Some medicines can cause side effects like drowsiness, dizziness, or mood changes. You should never feel like you have to “push through” the pain alone or rely too heavily on strong painkillers.

Physical Therapy: Moving Towards Relief

Staying active can help. Even if you’ve lost a limb, gentle movement and stretches can reduce pain. A physical therapist can guide you in exercises that improve circulation, strengthen muscles, and retrain your body to move without pain.

If you use a prosthetic limb, therapy can also help you get more comfortable with using it. The more naturally you can move, the less confused your brain will be.

Sometimes just improving your posture or changing the way you walk can reduce stress on the nerves and lower pain.

Therapists may also teach you relaxation techniques or breathing exercises to help calm your nervous system. Pain is often worse when we’re tense or anxious. Learning to relax can make a big difference, even if it seems small at first.

Mental and Emotional Support: Healing the Whole Person

Pain doesn’t just affect the body. It takes a toll on your mind, too. After trauma and amputation, it’s normal to feel grief, anger, sadness, or fear. These feelings don’t cause the pain—but they can make it worse. That’s why emotional healing is just as important as physical healing.

Talking to a counselor or therapist can help. So can connecting with others who’ve gone through similar experiences. You’re not alone, and there is no shame in asking for support. Even writing down your feelings or talking to a friend can help lift the weight a little.

Some people find that mindfulness, meditation, or even creative activities like painting or music help take the focus off the pain. The brain can only focus on so much at once. Giving it something positive to hold onto can lessen the space pain takes up.

Exploring New Treatments and Everyday Strategies That Work

Managing phantom limb pain isn’t just about getting through the day—it’s about building a life where pain doesn’t control everything. Over the years, newer and more advanced therapies have emerged, offering hope to many who didn’t find relief with traditional options.

At the same time, simple daily habits and consistent routines can quietly reshape the brain’s response to pain. This section brings both worlds together—new science and real-world strategies—to help you take control, one step at a time.

Virtual Reality and Augmented Feedback

Technology has come a long way in helping people manage pain that doesn’t seem to have a clear source. Virtual reality (VR) is one of the most promising tools out there. It works a bit like mirror therapy but adds more depth, sound, and movement.

Using VR, people can “see” and even “move” their missing limb in a virtual world. This helps the brain believe the limb is still there—and more importantly, that it’s functioning normally and without pain. Over time, this repeated experience can reduce or even stop the pain signals.

In some clinics, therapists guide patients through VR programs tailored to their pain patterns. But even simple versions of this therapy are being developed for use at home.

As this technology becomes more accessible, it could become a game-changer in managing phantom limb pain.

Other forms of feedback—like electrical stimulation, robotic arms connected to nerve signals, or sound-based biofeedback—are also being explored.

These may seem futuristic, but the idea behind them is very simple: give the brain new, real-time information that helps it let go of pain patterns.

Daily Movement and the Brain-Body Connection

One of the most overlooked tools in managing phantom pain is simple, daily movement. You don’t have to do anything extreme. But small, mindful movements—even of your shoulders, neck, or back—can help reset the brain’s sense of balance and body awareness.

Think of your brain as needing a daily reminder of what your body can do, not just what’s missing. The more you stay connected to your body, the less power the phantom pain has. This is why stretching, yoga, light resistance exercises, or even mindful walking can make a difference.

It’s not just about physical health. These kinds of movements help lower stress, improve sleep, and reduce tension—all of which are tied to pain levels.

Setting Up a Routine That Supports Healing

Pain often gets worse when life feels out of control. That’s why setting up a steady routine can quietly but powerfully reduce phantom pain over time.

This doesn’t have to be complicated. Even a simple morning routine that includes a few stretches, a short breathing exercise, or a walk outdoors can help regulate your nervous system.

Regular meals, good hydration, and a set sleep schedule also support your brain and nerves. When the body is well-rested and nourished, it handles pain signals better. Avoiding long hours of sitting or staying still can also help, since stiffness often triggers discomfort.

Even something as small as listening to music you enjoy, reading, or calling a friend at the same time each day can create a rhythm that helps the brain feel safer—and pain usually eases when the brain feels less threatened.

Sleep: The Quiet Weapon Against Pain

Sleep is one of the most powerful tools for healing the nervous system. But phantom pain can make it hard to fall asleep or stay asleep, leading to a cycle of more pain and more fatigue. Breaking this cycle is one of the most important long-term strategies.

Start by creating a sleep-friendly space. Keep your bedroom cool, dark, and quiet. Use soft blankets or pillows to support your limb, especially if the residual area feels sensitive.

Avoid screens for at least 30 minutes before bed, and if pain flares up at night, try a short breathing or relaxation exercise to calm the mind.

Some people find that gentle heat packs or soothing music help. Others may need to speak to a doctor about short-term medication support to improve sleep.

Remember, when you sleep better, your pain threshold goes up. You feel more in control, and your body can start to heal from the inside out.

Nutrition and Hydration: Small Shifts, Big Impact

The food and drinks you choose each day affect your brain and nerves more than most people realize. Certain foods can increase inflammation in the body, which may make nerve pain worse.

While there’s no special diet that “cures” phantom pain, eating in a way that supports nerve health can help reduce flare-ups.

Focus on whole foods like fruits, vegetables, whole grains, lean proteins, and healthy fats. Omega-3 fatty acids—found in fish, walnuts, and flaxseeds—may help calm inflammation. Vitamin B12 and magnesium are also important for nerve function.

Staying hydrated is equally important. Dehydration can lead to tension, muscle cramps, and even trigger nerve sensitivity. Make water a regular part of your routine, and try to limit things like caffeine, alcohol, and very salty or sugary foods, which can irritate the nervous system.

Even if changes are small—like swapping out one sugary snack for fruit or adding a handful of nuts to your breakfast—they add up over time.

Long-Term Tools for Living with Less Pain

Managing phantom limb pain is a long journey for many people. The goal isn’t just to “get rid” of the pain, but to build a life where pain doesn’t lead the way. That means combining the right tools, listening to your body, and staying connected to what matters to you.

You don’t need to be perfect. You just need to be consistent. Even on hard days, one small action—doing a stretch, practicing mirror therapy, or taking a few deep breaths—keeps you moving forward.

Some people find it helpful to track their pain patterns in a simple notebook. Write down when the pain happens, what it feels like, what might have triggered it, and what helped. Over time, you’ll start to notice patterns. That awareness gives you more control.

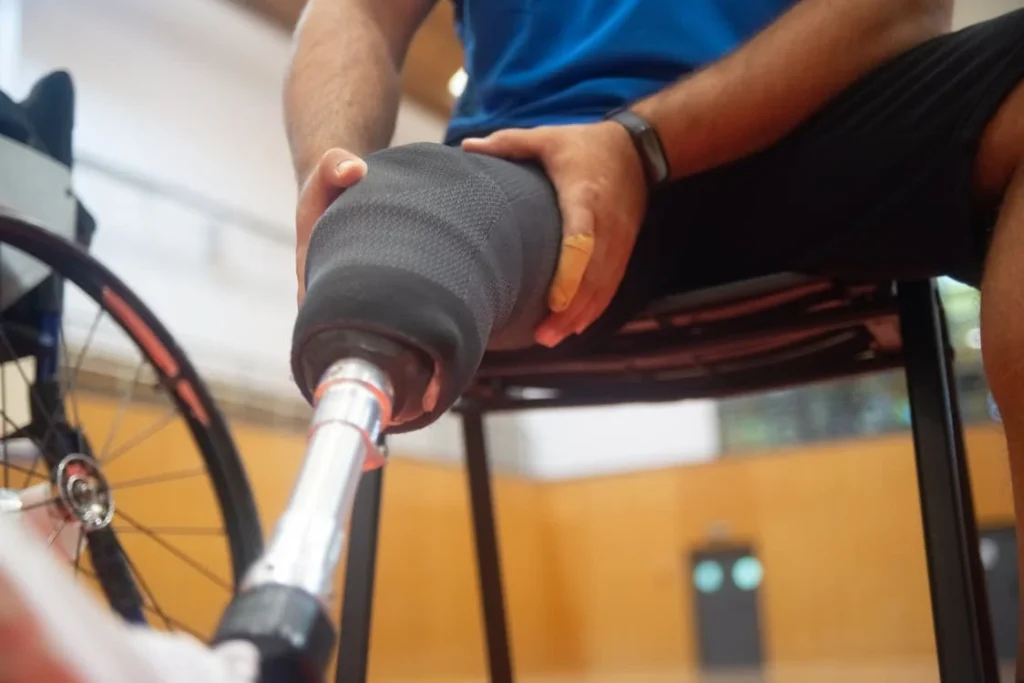

How Prosthetic Use Influences Phantom Limb Pain

Many people see prosthetics as tools for movement—and they are. But they can also become a key part of the solution when it comes to managing phantom limb pain.

This connection might not be obvious at first, but using a prosthetic limb can actually help retrain the brain, improve body awareness, and reduce pain over time.

It’s not just about walking again or picking things up. It’s about rebuilding the missing link between your brain and your body.

Reconnecting Brain and Body Through Movement

When a limb is lost, the body becomes disconnected from how it used to move. The brain’s map of the body is suddenly outdated. That missing space in the brain can create confusion and, in some cases, pain.

But when you start using a prosthetic limb—even if it’s just for short periods—it gives the brain new information.

Each step you take or object you hold with a prosthetic sends signals back to the brain that say, “This part is still here. It’s working.” Even though the limb is artificial, the brain treats movement as real.

Over time, this feedback can help the brain rewire itself in a way that reduces or replaces phantom pain.

This is especially true when the prosthetic is well-fitted and comfortable. A poorly fitting limb might cause more discomfort, which can confuse the brain even more. But a smooth, pain-free movement helps build new, healthier patterns.

Sensory Feedback and Advanced Prosthetics

Modern prosthetics are becoming more than just mechanical tools. Some newer models include sensory feedback systems—tiny sensors that mimic touch, pressure, or vibration. These devices don’t just help with function; they also provide missing sensory input to the brain.

That’s important, because phantom pain often develops from a lack of input. The brain expects to feel something, and when it doesn’t, it sometimes creates pain instead. Giving the brain even a small amount of sensory feedback can quiet those overactive pathways.

You don’t need the most high-tech prosthetic to benefit, either. Even basic prosthetics, when used regularly and correctly, provide enough movement and weight-bearing sensation to create brain changes.

Timing and Consistency Matter

Using a prosthetic early on—once the residual limb is healed and ready—can make a big difference. The sooner you begin to rebuild those movement patterns, the less time the brain spends reinforcing the old, painful ones.

But consistency matters just as much. If you only use your prosthetic once in a while, your brain doesn’t get the steady signals it needs to adapt. Daily use, even for short periods, helps create stable, long-lasting change.

This doesn’t mean you should push through discomfort or wear your prosthetic for hours without rest. It means making it a regular part of your day in a way that feels safe and manageable.

Emotional Impact of Regaining Movement

One of the lesser talked-about benefits of using a prosthetic is how it helps emotionally. Phantom limb pain doesn’t just affect the body—it often brings feelings of loss, frustration, or helplessness. Being able to stand, move, or hold something again can be a powerful emotional lift.

That emotional shift can, in turn, reduce stress and anxiety—two common triggers for pain flare-ups. When you feel more in control, more independent, and more engaged in life, the brain often calms down. It doesn’t “need” to send pain signals as a warning anymore.

Many people report that their phantom pain decreases after they start using a prosthetic regularly—not just because of movement, but because of the sense of possibility it brings.

Combining Prosthetic Use with Brain-Based Therapies

You can get the best results by combining prosthetic use with other brain-based strategies. For example, doing mirror therapy while wearing a prosthetic, or practicing mindfulness after physical therapy, can boost the effects.

Some rehabilitation programs now blend physical training, cognitive exercises, and even gamified prosthetic training. These types of multi-layered approaches can accelerate brain rewiring and reduce both pain and frustration.

Even home-based programs that involve using a prosthetic while engaging in goal-driven activities—like reaching for a cup, walking around your house, or playing a simple game—can give the brain positive feedback and reduce pain over time.

Building Confidence with Support

It’s normal to feel uncertain when first using a prosthetic, especially after trauma. The device may feel unfamiliar. You may worry about balance or discomfort. These feelings are common, but they can fade with time and support.

Working with a skilled prosthetist or therapist can make a huge difference. They can help adjust the fit, teach you how to use the device safely, and create small goals that build confidence.

And as confidence grows, the brain starts focusing on movement and possibility—not pain.

Over time, the prosthetic becomes more than just a tool. It becomes part of how your brain understands your body again. And that understanding is what helps silence phantom limb pain at its source.

The Role of Caregivers and Family in Managing Phantom Limb Pain

Living with phantom limb pain can be a lonely experience. It’s a type of pain that can’t be seen, touched, or easily explained. For loved ones standing on the outside, it can be hard to know how to help.

But support from family and caregivers often makes a bigger difference than any treatment plan. It’s not just about physical help—it’s about being seen, heard, and understood.

Helping someone cope with invisible pain is not always easy. But when support is offered in the right way, it can reduce stress, improve healing, and even lower the intensity of the pain itself.

Understanding the Experience Without Trying to “Fix” It

The first and most powerful thing a caregiver can do is simply listen. Phantom limb pain is real, but it can sound strange to those who haven’t felt it. Saying things like “but your limb isn’t there anymore” or “maybe it’s just in your head” (even with good intentions) can feel dismissive.

Instead, acknowledging the pain as real and valid creates safety. Phrases like, “I can’t imagine how that feels, but I’m here with you,” carry more weight than any advice. It gives the person space to speak about their pain without needing to prove it.

Trying to “fix” the pain—by suggesting endless treatments or dismissing what hasn’t worked—can feel overwhelming. Often, just being present and emotionally available is more valuable than offering solutions.

Creating a Supportive Routine Without Taking Over

Phantom limb pain is unpredictable. It might come and go with no warning. Creating a steady, calming daily routine helps reduce mental strain and gives the nervous system something to anchor to.

Caregivers can gently help by supporting healthy habits—regular meals, gentle reminders to hydrate, and encouragement to move or stretch when possible.

But there’s a fine line. If support turns into control—like hovering, over-helping, or making every decision—it can take away the sense of independence the person is trying to rebuild.

The goal is partnership, not protection. It’s okay to ask: “Would it help if I reminded you to do mirror therapy today?” or “Want me to sit with you while you do your exercises?” This invites collaboration and avoids pressure.

Watching for Emotional Warning Signs

Phantom limb pain is closely tied to emotional well-being. When pain is persistent, it can lead to frustration, isolation, or even depression. Caregivers are often the first to notice changes in mood, energy, or sleep that might indicate a deeper emotional struggle.

Without being intrusive, simply checking in can open the door. Say things like, “I’ve noticed you seem more tired lately—want to talk about it?” or “I’m here if you’re ever feeling overwhelmed.”

Sometimes the person might not want to talk, and that’s okay. What matters is knowing someone is there when they’re ready.

If emotional distress grows or begins to interfere with daily life, gently encouraging professional support—like a counselor or peer support group—can be a caring next step.

Encouraging Prosthetic Use Without Pressure

Using a prosthetic for the first time after trauma can be emotional. There’s pride, but also fear, sadness, and sometimes discomfort. Family members often want to cheer on progress but may not realize how complex it feels for the person wearing it.

Instead of pushing, be encouraging in subtle, practical ways. Offer help with strapping or adjustments if needed.

Celebrate small milestones—like standing a little longer or walking a few more steps—not with big fanfare, but with quiet encouragement. “That looked really steady today” goes much farther than “You should wear it more.”

Understand that some days will be harder than others. The goal is to support a healthy rhythm, not perfect consistency.

Managing Caregiver Stress and Burnout

Being a caregiver—especially for someone in chronic pain—can be deeply meaningful, but also draining. Many caregivers put their own needs on hold. Over time, that leads to burnout, frustration, or guilt.

Taking care of yourself is not selfish. It’s essential. Make space for your own breaks, hobbies, and mental health. If you’re rested and grounded, your support becomes more sustainable and genuine.

You’re also modeling something important: that it’s okay to ask for help and take care of your needs. The person you’re supporting will likely respect and reflect that balance back over time.

Sharing responsibility with other family members, friends, or professionals—like physical therapists or counselors—can ease the pressure. Even short breaks can recharge your emotional energy.

Building a Shared Vision of Progress

One of the best things families can do is focus not only on what was lost, but what can still be built. Phantom pain doesn’t erase the future. Instead of getting stuck in frustration, work together to create a shared picture of what healing and progress could look like.

Set small goals together. Make space for joy and laughter, even on hard days. Remind each other that healing is not a straight line. Some days will be about managing pain.

Others might be about trying something new, even if it’s just walking in the park or preparing a favorite meal together.

When both the person with phantom limb pain and their caregiver feel like they’re on the same team—facing forward, not backward—it creates hope. And hope itself is a kind of medicine.

Cultural Beliefs and Social Stigma Around Phantom Limb Pain

In many cultures, including across parts of India and South Asia, the way we talk about pain, disability, and the body isn’t just medical—it’s personal, spiritual, even moral.

This can have a powerful impact on how someone experiences phantom limb pain, how they cope with it, and whether they feel supported or judged by those around them.

While medicine focuses on nerves, brain maps, and rehab protocols, the social environment—family beliefs, community attitudes, even superstitions—can play just as big a role in shaping recovery.

And when it comes to phantom pain, which is invisible and hard to explain, those cultural layers can either help a person heal or leave them feeling silenced.

When Pain Is Seen as Imaginary or a Sign of Weakness

One of the hardest parts of phantom limb pain is that you can’t “see” it. There’s no swelling, no wound, no visible proof. In some families or communities, this can lead to doubts: “Are you sure you’re not just imagining it?” or “You need to be stronger, stop thinking about it.”

This kind of reaction, even when meant with kindness, can make a person feel dismissed or ashamed. They may stop talking about their pain altogether, keeping it to themselves, even as it worsens.

Emotional isolation like this doesn’t just hurt mentally—it can make physical pain harder to manage, because the brain interprets emotional distress as part of the danger signal.

In some cases, people begin to blame themselves for not “healing faster” or “being tough enough.” This internalized guilt can block progress, delay treatment, and damage confidence. It turns recovery into a private struggle instead of a shared journey.

Spiritual Interpretations of Pain and Loss

In traditional cultures, physical suffering is sometimes tied to ideas of karma, past life actions, or divine tests. Some may believe that losing a limb—or the pain that follows—is a punishment or a destiny that must be silently endured.

While faith can be a strong source of comfort and resilience, it can also, in some contexts, stop people from seeking help.

If pain is seen as something that must be tolerated to show spiritual strength or fulfill a karmic path, the person may feel pressure to suffer quietly. They may avoid therapy or medications because they worry it shows weakness or interrupts fate.

But science and spirituality don’t have to be at odds. In fact, many people find peace in both. Spiritual practices like meditation, prayer, or rituals can coexist with modern treatments.

What’s important is giving people permission to seek relief without guilt—knowing that healing does not dishonor their faith.

Gender Roles and Hidden Struggles

Gender expectations in many parts of the world add another layer. Men may feel they must hide their pain to appear “strong,” especially if they are seen as providers.

Women may feel ashamed to speak about their bodies or their emotional pain, especially in joint family systems where personal space is limited.

This silence often delays recovery. Pain that goes unspoken becomes pain that isn’t treated. And untreated phantom limb pain can spiral into long-term physical and mental distress.

Caregivers and health workers must be sensitive to these unspoken pressures. Creating safe spaces—where pain can be talked about without judgment—can change everything.

How Community Attitudes Affect Confidence

In many rural and even urban areas, people with limb loss still face stigma. They may be viewed with pity, avoidance, or even fear.

In some traditional beliefs, physical disability may carry a social label—“unlucky,” “incomplete,” or “less capable.” This can damage self-esteem and discourage people from using prosthetics, attending rehab, or rejoining work or school.

For someone dealing with phantom pain on top of all this, it can feel like a double burden—one physical, one social.

Changing this means starting conversations, not just with doctors, but in homes, schools, workplaces, and religious spaces.

It means helping people understand that phantom limb pain is a medical condition, not a flaw or weakness. That losing a limb does not erase a person’s value. And that asking for help is a form of strength, not shame.

Building a Culture of Compassion and Understanding

Cultural shifts don’t happen overnight, but they start with small, human moments. When families listen with empathy. When a neighbor encourages someone to go for therapy.

When health workers use simple words, not medical jargon. When support groups include conversations in local languages. These small shifts add up to something powerful.

For someone with phantom limb pain, knowing they’re not alone—and that their pain is real—can be as healing as any medicine.

Public education campaigns, media representation, and local storytelling all play a role in this. So do schools that include disability awareness, workplaces that welcome amputees, and clinics that offer not just treatment, but dignity.

Conclusion

Phantom limb pain is complex, unpredictable, and deeply personal. Though it begins in the body, it reaches into the mind, emotions, and everyday life. But it is not something you have to simply live with. Through a combination of therapies, consistent routines, emotional support, and community understanding, it can be managed.

Whether it’s mirror therapy, prosthetic use, movement, mindfulness, or simply being heard—every small step adds up. Healing may not follow a straight line, but progress is always possible. What matters most is finding what works for you and building a support system that believes in your journey.

Pain may be part of the story, but it doesn’t have to define it.