Helping someone use a bionic limb is not just about fitting a device. It’s about helping their brain learn something new. Neural learning is the hidden key that helps users move, control, and trust their prosthetic hand.

As a clinician, understanding how the brain works with a bionic limb can help you guide your patients better. It gives you insight into their progress, struggles, and success. It also helps you become more effective in your role—because the mind and body are always connected.

In this article, we’ll explore what neural learning really is, why it matters in bionic limb use, and how you can support it during prosthetic fitting and rehab.

Let’s begin by understanding how the brain and bionic hand work together.

How the Brain Connects to a Bionic Limb

The Brain Remembers What Was Lost

When a limb is lost—whether due to trauma or disease—the brain doesn’t erase the memory of that body part. It still has a map of the missing hand or arm. This is called the “body schema,” and it stays active even after amputation.

That’s why many users feel sensations from their missing hand, often called phantom limb sensations. The brain still sends messages to the hand that is no longer there. This memory becomes a bridge for learning how to use a prosthetic.

As a clinician, it’s helpful to explain this to your patients. It reassures them that their brain still wants to move—and that this is a good thing.

Myoelectric Signals: The Path to Control

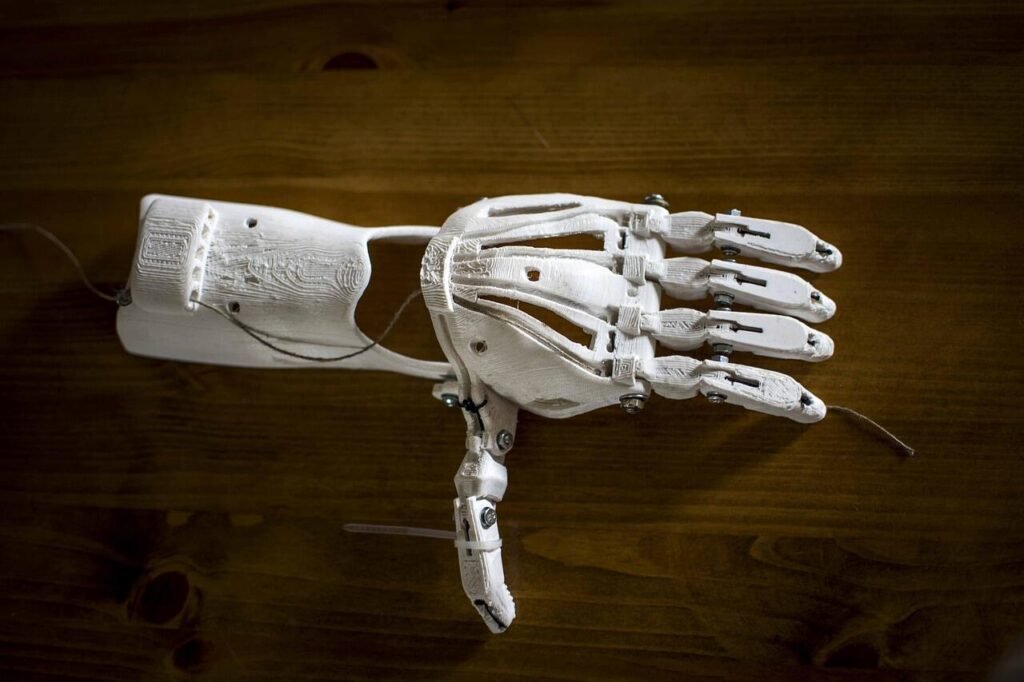

Bionic limbs like Grippy™ work using muscle signals from the residual limb. These are called myoelectric signals. They are small electrical impulses that muscles naturally produce when trying to move.

Even after amputation, the remaining muscles can still fire when the user thinks about moving their hand. These signals are picked up by sensors in the prosthetic. The device then translates these into motion.

But here’s where neural learning plays a key role. The user has to retrain their brain to send these signals correctly. It’s like teaching the mind a new way to talk to the body. At first, it might feel slow or awkward. Over time, it becomes faster and smoother.

Building a New Brain-Hand Connection

Using a prosthetic for the first time can feel strange. It doesn’t move like the hand the person once had. The weight, the grip, and the delay might feel foreign.

But the brain is adaptable. This is where neuroplasticity steps in.

Neuroplasticity is the brain’s ability to change. It can build new pathways, create new routines, and shift how it controls the body. With repeated practice, the brain slowly begins to treat the bionic hand as a real part of the body.

This connection isn’t just about motion. It’s also about trust. The user needs to believe they can move the hand, control it, and rely on it.

You can support this process through encouragement, structured tasks, and steady follow-up.

Neural Learning Is Not Automatic

It Takes Time and Repetition

Neural learning is not something that happens all at once. It takes time, effort, and regular use of the prosthetic.

Just like a baby doesn’t learn to walk in one day, a person doesn’t instantly gain full control over a bionic hand. The brain needs to explore, try, and repeat new movements many times before they feel natural.

That’s why early training is so important. Every small action—gripping a spoon, lifting a light object, pressing a button—sends signals to the brain.

With each attempt, the brain gets better at making the right connections. Eventually, those movements become automatic.

The Brain Learns What It Practices

The more a user practices specific movements, the better the brain becomes at doing them. But this also means the brain learns bad habits if they are repeated.

That’s why correct guidance during the learning phase is important. If a user repeatedly performs a motion in an incorrect way, the brain will remember that as the “normal” way.

You can prevent this by observing closely, correcting gently, and providing clear feedback. Simple adjustments—like helping them hold an object at the right angle—can help their brain learn faster and more accurately.

Feedback Makes Learning Stronger

One of the most powerful ways to improve neural learning is through feedback.

When a user feels something—like the grip of the prosthetic, the vibration from a touch sensor, or even a visual cue from watching their own hand move—the brain responds faster.

Our Grippy™ hand has Sense of Touch™ feedback. This gives users a signal when they grasp something, helping the brain know what just happened. This small feedback loop builds confidence and speeds up brain adaptation.

You should encourage users to pay attention to this feedback. Over time, the brain begins to expect it. This expectation makes movements feel more natural and connected.

Emotional State Shapes Neural Response

Fear Slows Progress

When users feel afraid or frustrated, their brain goes into a protective state. It may shut down learning pathways, or resist new changes. This slows down the entire adaptation process.

Some users may feel anxious about failing, dropping objects, or feeling different. This is normal. But it’s important to help them feel safe and supported.

The more relaxed they are, the more open their brain becomes to learning.

As a clinician, you set the emotional tone. If you stay calm, patient, and encouraging, the user will feel more confident in their ability to improve.

Confidence Boosts Learning

On the other hand, when a user feels proud of what they’ve done—even something small—the brain responds with stronger connections.

Confidence acts like a signal booster. It tells the brain, “This works. Keep doing it.”

This is why celebrating little wins is not just nice—it’s necessary.

Each time the user completes a task, give them positive reinforcement. Tell them what went well. Show them their progress. These moments become anchors in the brain’s learning process.

Motivation Drives Consistency

Neural learning doesn’t just depend on practice—it depends on repeated, meaningful practice.

That’s why motivation matters.

If the task feels important to the user—like holding a spoon to eat, or turning a key to unlock a door—the brain pays more attention.

Let users choose the tasks they care about most. Build exercises around real goals. This makes practice feel purposeful, not like a chore.

And it keeps the user coming back—even on tough days.

The Clinician’s Role in Guiding Neural Learning

More Than Fitting a Device

Fitting a prosthetic is not just a physical task. It’s also a mental and emotional journey. As a clinician, you’re not only setting up the device—you’re helping build a new relationship between the user’s brain and their prosthetic hand.

Every interaction you have with the user can either help or slow that learning process. The way you guide, speak, and encourage makes a real difference in how their brain responds.

You are the bridge between the device and the person’s confidence.

Teach the Brain, Not Just the Body

Sometimes, it helps to think like a teacher. When guiding a user, remember that you’re not only working with their muscles—you’re also speaking to their brain.

Start with very simple movements. Help the user understand what they should be thinking about when they try to move the hand. Is it a squeeze? A lift? A flex?

Using short, clear cues helps the brain connect the intent with the outcome. Over time, this makes the motion smoother.

Always remind users that the brain needs practice to build control. If a movement feels slow today, that’s okay. Speed will come with time.

Structure Sessions to Support the Brain

The way your training sessions are set up can shape how well neural learning happens. Short, focused sessions tend to work better than long, tiring ones—especially in the beginning.

Try breaking the session into small steps. Start with a warm-up. Move to a new task. End with something they’ve already succeeded at.

This gives the brain a clean beginning, a chance to try something new, and a win at the end. It helps the user leave with a sense of progress, not frustration.

Avoid rushing through multiple tasks. The brain benefits more from doing one task correctly than from trying five tasks poorly.

Repeat, But With Variation

Repetition is important. But repeating the same task in the exact same way can become dull for the brain.

Try changing the context slightly.

If they’re learning to grip a cup, try different sizes. Try a glass cup, a plastic bottle, or a metal can. This helps the brain adapt in different ways and builds more flexible control.

You can also shift the environment—use a table, a kitchen counter, or even a chair. Changing the setting adds just enough variety to keep the brain engaged without creating confusion.

Use the Stronger Side to Support the Weaker

Many users still have one natural hand. Use it during training.

Ask the user to perform a task using both hands together. This helps the brain send signals to both sides of the body. It also supports coordination and speeds up learning.

You can even ask them to watch their natural hand move, then imagine the same motion in the prosthetic. This activates mirror neurons—special brain cells that help copy movement—and encourages better control.

These small tricks make a big difference in how the brain forms new patterns.

Troubleshooting When Progress Slows

Recognizing Mental Fatigue

Sometimes, users hit a wall. They stop improving. They get tired, frustrated, or even avoid using the prosthetic.

This can be a sign of mental fatigue. The brain has been working hard, but now it needs a break or a new approach.

Don’t panic. This is common. Step back and simplify the task. Go back to something they’ve already mastered. Remind them of how far they’ve come.

This helps recharge their brain and rebuild their belief in progress.

When Frustration Creeps In

If a user starts saying things like “I’ll never get this” or “It’s too hard,” they might be stuck in a negative loop.

This mindset can block neural learning. The brain becomes less flexible when it’s under stress or self-doubt.

Your role here is to help shift their focus. Instead of pushing harder, try changing the energy of the session.

Ask questions like, “What felt a little easier today?” or “Can we try something fun?” These small shifts in tone can break the loop and restart motivation.

Even humor can help. A light-hearted moment can reduce stress and open the brain back up to learning.

Reassess the Fit and Settings

If the user is doing everything right but still struggling, check the basics.

Is the prosthetic too heavy? Is the socket uncomfortable? Are the myoelectric sensors in the right place?

Sometimes, even a small physical issue can block progress. The user may not say it directly, but they might be compensating without realizing it.

Revisit the fit, review the signal strength, and consider making small adjustments. A better physical experience can restart mental progress.

Long-Term Neural Learning: What Happens After the Clinic

The Brain Keeps Adapting at Home

Many clinicians assume that the brain’s biggest learning happens during the early weeks of prosthetic training. But in truth, the most meaningful progress often takes place at home—when the user starts living with the device.

When the user opens a jar, lifts a bag, or tries brushing their teeth with the prosthetic, their brain is still learning. These daily challenges create new neural links every time the hand is used.

This is why follow-up care matters. Staying in touch with users, even after they’ve been discharged, helps ensure they continue making progress.

Encourage users to use their bionic limb in small, everyday ways—not just for rehab exercises. The more naturally it fits into their routine, the deeper the brain adapts.

Make Room for New Goals

As a user gains confidence and skill, their goals often shift. What started as “just being able to hold something” may grow into more complex desires—like typing, cooking, or playing an instrument.

This is a good sign. It shows that their brain is moving from basic control to fine-tuned coordination.

You can support this by adjusting the training plan to match their new goals. Add tasks that require precision, balance, or speed. Encourage new challenges. Let them push their limits, one step at a time.

Even small upgrades—like switching grip patterns or introducing dual-task activities—can keep the brain active and engaged.

Help Them Reflect on Progress

Sometimes users forget how far they’ve come. They only see what they still can’t do.

You can help by guiding them to reflect on their progress. Ask questions like:

- What was hard for you last month that feels easier now?

- What’s something new you’ve done with your hand recently?

- What’s one task you didn’t think you could do, but you did?

These moments help reinforce the brain’s progress. They also boost motivation.

If possible, keep short video clips of their training from early sessions. Watching those again can be powerful. Seeing their own journey gives them pride and deepens the brain’s sense of ownership over the limb.

Empower Them to Self-Train

Once a user leaves formal rehab, they should still have tools to continue training.

Encourage them to create their own “mini sessions” at home. These could be 5-10 minutes each day, focusing on one or two small tasks.

You can also suggest using simple objects around the house—water bottles, spoons, towels—to practice grips, lifts, and releases.

If they’re using a device like Grippy™, remind them to pay attention to the feedback from the Sense of Touch™ system. Even outside the clinic, this feedback helps the brain stay connected to the limb.

Over time, these short, focused efforts lead to stronger long-term brain control.

How Technology Can Help Neural Learning

Smart Feedback Enhances the Brain-Device Loop

One of the most valuable tools in modern prosthetics is real-time feedback.

When a device responds to the user’s effort and gives feedback—through touch, pressure, or motion—the brain builds faster, more accurate patterns.

In our Grippy™ system, the feedback doesn’t just tell the user what they’re doing—it teaches the brain what success feels like.

This learning-through-feeling makes the user more confident and makes the prosthetic feel more like a natural part of their body.

As a clinician, encourage the user to focus on this feedback during training. Ask them to notice how it feels when they grip something or release it.

These small sensory moments matter.

Gamified Rehab Makes Learning Fun

Repetition can get boring, especially when the tasks feel mechanical. That’s why our Gamified Rehab App is designed to keep users engaged.

It turns training into play. Each game is built around real movement goals—grip, hold, flex, release—while tracking progress in the background.

This playful approach is not just fun—it’s strategic. It rewards effort. It gives users something to aim for. And most importantly, it keeps their brain excited to learn.

If your users have access to the app, suggest they use it regularly, even if just for 10 minutes a day.

The brain loves rewards. And with every level completed, the user gets one step closer to full control.

Data Helps Clinicians Guide the Journey

One benefit of digital prosthetic systems is that they can track usage data—like grip strength, duration of use, and training patterns.

This data gives you, the clinician, insight into what’s working and what’s not.

You can spot gaps in progress, adjust the training plan, and help the user overcome any hidden roadblocks. It also gives you a tool to celebrate progress with clear evidence.

Even something as simple as “You’ve used your hand for 30 minutes a day this week—double what you did last month” can motivate the user and show them their growth.

Shaping the Future: Your Role in Bionic Success

Clinicians Are Partners in Neural Change

At Robobionics, we believe that every clinician is more than just a technician or trainer. You are a partner in neural transformation.

You’re helping someone’s brain rewrite the rules. You’re giving them not just movement—but hope, control, and identity.

That’s powerful work.

So much of what the user achieves comes from how you guide, support, and believe in them.

With every smile, every tip, and every patient moment—you are literally helping reshape a human brain.

That’s not just care. That’s science in action.

Putting It All Together: A Clinician’s Daily Practice

Begin With Empathy

Before any sensor is tested or socket is adjusted, the first step in helping a user is simple: listen.

Empathy opens doors the brain can’t. When a user feels seen and heard, they’re more open to trying, failing, and trying again. That emotional safety creates space for the brain to learn.

Ask about their fears. Ask about their goals. Ask what they’re excited to do again. These questions don’t just build trust. They create a learning environment the brain responds to.

Every user is different. What worked for one might not work for another. And that’s okay. Your willingness to adapt makes all the difference.

Slow Is Fast

There’s often a rush to “get results” in rehab. But neural learning doesn’t follow deadlines. It follows patterns—and those patterns take time to settle.

Going slow, especially in the beginning, is not falling behind. It’s setting a strong foundation. Let the user get used to the weight, the movement, and the feel of the hand. Let the brain explore before it performs.

You’ll often find that those who start slow end up progressing faster in the long run. Their brain builds a deeper, more stable control that lasts beyond the clinic.

Train With Purpose, Not Pressure

Your sessions don’t need to be packed with tasks. They just need to be meaningful.

Even something as small as helping the user pick up their phone or hold a toothbrush is powerful when done with care. Choose tasks that reflect their life, not just textbook exercises.

Avoid overwhelming them with information or movement. Keep it focused. Explain the goal of each action. Connect it to something that matters.

This is how you turn training into progress—and effort into empowerment.

Stay Curious, Stay Connected

The field of prosthetics is growing. Every year brings new tools, smarter devices, and deeper research into how the brain adapts.

As a clinician, staying curious helps you stay ahead.

Explore new training methods. Learn from peers. Share what you’ve seen work. And most importantly—stay connected to your users, even after the fittings are done.

Follow up. Celebrate their milestones. Be the person they turn to not just for adjustments, but for encouragement.

That relationship is often what keeps a user moving forward—long after the sessions end.

Closing Thoughts: You’re Changing Lives, One Brain at a Time

What makes someone succeed with a bionic limb isn’t just the technology. It’s the team around them. It’s the clinician who took the time to explain the process. It’s the one who listened. Who guided. Who believed.

Neural learning is invisible. You can’t see the connections forming in the brain. But they’re there—shaping every movement, every smile, every breakthrough.

You’re part of that. And your role is more powerful than you might realize.

At Robobionics, we see you. We admire your work. And we’re here to support you with technology that listens to the brain, adapts to the user, and grows with each step.

If you’re a clinician who wants to learn more about how Grippy™ and our other products support neural learning, or if you want to see our tools in action, we’d love to show you.

Book a one-on-one session with our clinical team at:

https://www.robobionics.in/bookdemo

Let’s continue changing the future of care—one user, one hand, one hopeful brain at a time.