Explaining bionics to patients can feel overwhelming—especially when they’re already adjusting to big changes in their body, routine, and emotions.

They may be nervous. They may be hopeful. But most of all, they’re trying to understand: Will this help me feel normal again?

As a clinician, your words matter. What you say can shape how the patient feels about their new limb, how committed they stay during rehab, and how well their brain begins to connect with the device.

In this guide, we’ll break down how to talk about adaptive bionics in a way that makes patients feel confident, informed, and supported. You’ll learn how to explain smart prosthetics using stories, visuals, and simple comparisons—so your patients understand not just how the device works, but how it works for them.

Let’s begin by answering the question most patients have but are too afraid to ask: What even is a bionic hand—and how does it know what I want to do?

What Is a Bionic Hand, Really?

It’s Not a Robot—It’s a Smart Helper

Many patients hear the word “bionic” and imagine something out of a movie—metal, wires, maybe even something mechanical and cold. But a bionic hand is not a robot.

It’s a smart helper. One that listens to your body, learns how you move, and supports you like a teammate.

It’s powered by tiny signals your muscles still send, even after amputation. These signals are real—and they’re strong enough to control a hand that opens, closes, and grips.

You’re not operating a machine. You’re teaching it how you move.

The Hand Doesn’t Think for You. It Thinks With You

A lot of patients ask, “How does it know what I want to do?”

The answer is simple: it doesn’t at first—but it learns.

When you flex your muscles in a certain way, the bionic hand feels those signals. Over time, it starts to recognize patterns—like when you’re trying to hold a glass or turn a doorknob.

This is called adaptive control. It means the hand gets better at understanding you the more you use it. Just like how your phone gets better at predicting your words, the bionic hand gets better at responding to your body.

You and the hand learn together.

Explaining Adaptive Control in a Way That Makes Sense

Use a Real-Life Analogy

To make adaptive control easier to explain, compare it to something familiar.

Here’s a good one: “Imagine you’re teaching someone how to dance with you. At first, they step on your toes. But the more you dance together, the better they move with you. That’s how your bionic hand learns to follow your lead.”

This helps the patient understand that they’re not learning alone. The device is learning, too.

And that changes how they feel about mistakes. Instead of thinking “I’m doing it wrong,” they start thinking “We’re still learning.”

That shift builds confidence.

Emphasize That There Is No One ‘Right Way’

Some patients worry they won’t “get it right.” They may feel pressure to control the hand perfectly from day one.

Reassure them that adaptive bionics are built for their body—not a perfect one. If they move differently than someone else, that’s okay. The hand will adjust.

Say something like, “This hand doesn’t expect perfection. It expects practice. It’s made to work the way you move.”

That small sentence can remove a lot of fear.

What Patients Really Want to Know

“Will It Feel Like My Real Hand?”

This is a big one.

Be honest, but hopeful. Tell your patient, “It won’t feel exactly the same—but it can become something your brain accepts as part of you.”

Explain that at first, the brain doesn’t know what to make of the new hand. But with practice and the right feedback, the brain begins to include the hand in its “body map.”

Say, “Over time, your brain stops thinking of it as a tool—and starts treating it like it belongs.”

This not only answers the question, but gives the patient a goal to work toward.

“What If I Get Tired or Struggle?”

Let them know that struggling is part of the process.

Say something like, “That’s exactly why adaptive bionics exist. If your muscles are tired, the hand adjusts. If you send a weak signal, it still tries to help.”

Patients often feel pressure to be strong every day. But adaptive control gives them permission to have off days—and still succeed.

That reassurance can be the reason they stick with it.

Building Trust Between the Brain and the Bionic Hand

Explain It Like a Conversation Between Body and Device

One of the simplest ways to help a patient understand adaptive bionics is to describe it as a conversation. Their brain sends a message. The hand listens and responds. Over time, that conversation gets smoother.

You can say, “At first, the messages from your brain might sound like whispers. But the more you practice, the louder and clearer they get. And the hand learns how to listen better too.”

This kind of explanation makes the process feel like teamwork. It turns an unfamiliar device into a friendly partner.

Let Them Know the Brain Is Already Helping

Many patients don’t realize how powerful their brain still is after an amputation. They might think, “I don’t have a hand anymore—how can I move anything?”

That’s the perfect moment to say, “Your brain still remembers your hand. It still sends signals. The only thing missing was something to receive them. That’s what the bionic hand does—it catches those signals and helps turn them into movement.”

When patients understand their brain is already working in their favor, it often gives them hope. They’re not starting from zero—they’re just reconnecting.

The Power of Feeling Progress, Not Just Seeing It

Early Wins Make a Big Difference

During the first few days or weeks of using a bionic hand, progress can feel slow. The movements may be small, but the mental effort is huge. That’s why it’s important to highlight every little win.

Say things like, “You opened your hand smoother today than yesterday. That means your brain and the hand are already syncing up.”

This kind of feedback helps the patient stay motivated. It teaches them to celebrate small steps—which is exactly how long-term success is built.

Adaptive Control Makes Every Attempt Count

In older prosthetic systems, if a signal wasn’t perfect, nothing would happen. That meant a lot of failed attempts, which could feel discouraging.

But with adaptive bionics, even small or shaky signals are noticed and used. This helps the patient feel like their effort matters.

Let them know: “This hand is made to learn from every try. So even when it doesn’t move exactly how you hoped, it’s still learning what you want.”

That makes each session feel valuable. And value leads to commitment.

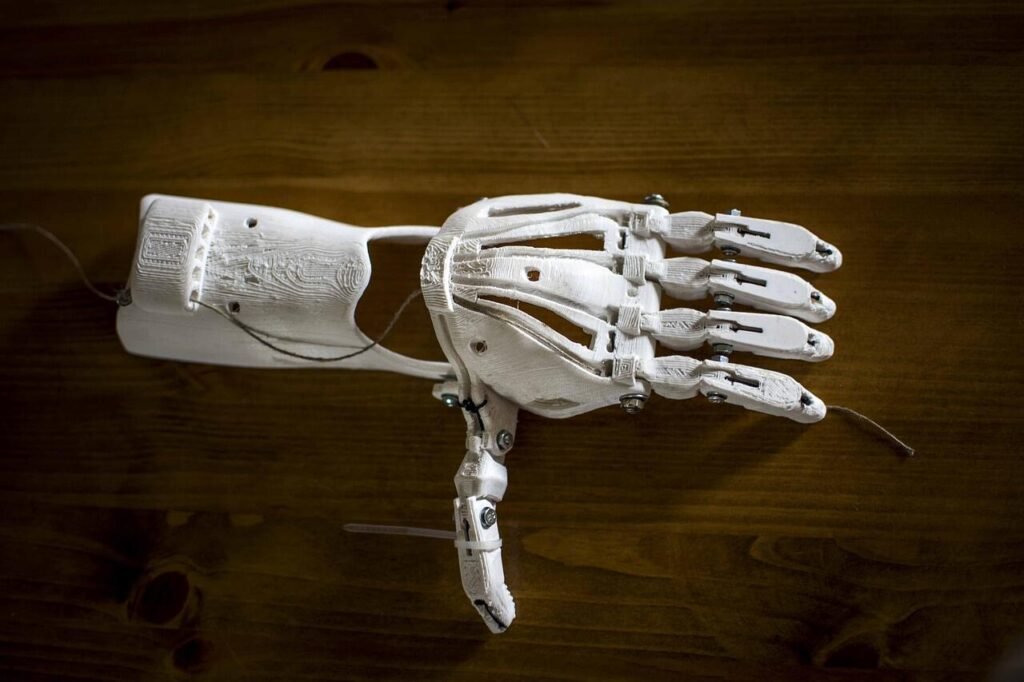

How to Introduce Adaptive Bionics During Fitting

Keep the Language Personal, Not Technical

When you introduce the device, avoid starting with specs or features. Start with the person.

Say, “This hand is going to learn your movements. It’s not about perfect control—it’s about building comfort over time.”

If they’re curious about the tech later, you can always explain the details. But your first goal is to make them feel safe, not smart.

The less pressure they feel to “get it right,” the more open they’ll be to learning.

Let the User Lead the Experience

During fittings, allow the patient to feel in control. Ask them how the motion feels. Ask what seems easy, what seems off.

Say, “You’re the one driving this—we’re just helping the hand catch up.”

This puts the focus on the patient’s experience rather than the device’s capabilities. It builds trust between the person, the prosthetic, and the clinician guiding the journey.

Managing Emotions and Expectations

Let Patients Know It’s Normal to Feel Unsure

Getting a bionic hand is a big emotional step. Even if someone is excited, they might still feel nervous, confused, or even disappointed at first.

You can ease those emotions by saying, “It’s okay if this feels strange. Your brain is meeting something new—and it takes time for the two of you to get in sync.”

This gives patients permission to feel what they’re feeling, without guilt. It also reassures them that discomfort doesn’t mean failure.

Every feeling is part of the process.

Be Honest About the Learning Curve

Some patients may expect the hand to work perfectly right away. When it doesn’t, they get discouraged and blame themselves.

It helps to set realistic expectations early on. Try saying, “Just like learning to write with your non-dominant hand, this takes time. But each time you try, your brain gets better—and so does the hand.”

Honesty builds trust. When patients know what to expect, they’re more likely to stick with the process instead of walking away when it gets hard.

Helping Patients Reconnect With Their Body

Explain That the Hand Can Become Part of Them

For many users, the prosthetic feels like a foreign object at first. This is totally normal. But the goal is to make it feel more like a natural extension of the body.

You might say, “Right now, it feels like the hand is something you wear. But soon, your brain may start to treat it like something you own. That’s what we’re working toward together.”

This helps patients understand that the connection will grow. It also gives them a new mindset—something to look forward to.

Use Mirror Language and Visualization

Simple tools like mirror therapy or guided imagery can make a big difference early on.

Encourage patients to imagine using their hand even when they’re not wearing it. Say, “Try picturing yourself turning a doorknob or picking up a glass. Even just imagining those movements helps your brain prepare.”

These mental exercises speed up how the brain adapts to the new hand. They also give the patient a sense of control—even outside therapy sessions.

Storytelling as a Teaching Tool

Share Examples of Other Patients

When patients feel alone in their struggle, stories can make all the difference.

Without naming names, you can share stories like, “One of my patients also struggled with gripping at first. But after two weeks, he could hold a coffee mug and stir sugar with one hand. That progress made him believe he could do more.”

Stories help patients imagine a future version of themselves. They replace fear with possibility.

And possibility is powerful.

Use “You” More Than “It”

Instead of saying, “The device will grip like this,” try, “You’ll be able to grip like this.”

This subtle shift places control back in the patient’s hands. It reminds them that they are not passive. They are the active force guiding the journey.

The more you make the language about them, the more they connect with what’s possible.

Keeping Patients Engaged Over Time

Give Them Simple Tasks They Care About

Adaptive bionics improve with use. But use only happens when the patient stays motivated.

One effective way to do this is to link the hand to activities they love. If someone enjoys cooking, focus on kitchen tasks. If they garden, practice gripping small tools or holding a hose.

Say, “Let’s teach the hand how to help you do what you love.”

This makes the practice feel personal. And personal tasks have more emotional weight—which helps the brain learn faster.

Track Progress in Small Ways

Success doesn’t have to be big to be meaningful. In fact, the brain builds faster through small, repeated wins.

Encourage patients to keep a simple journal. Let them note moments like, “Today I picked up a spoon without help,” or “I put my shirt on using both hands.”

These little notes add up to a big story—a story of growth.

And when the patient can see that growth, they stay committed.

Making Complex Concepts Easy to Understand

Break Big Ideas Into Everyday Moments

Sometimes clinicians try to explain bionic features in technical terms like “pattern recognition,” “signal mapping,” or “feedback loops.” While these are accurate, they’re rarely helpful for a new user.

Instead, translate these concepts into simple examples from everyday life.

For instance, instead of “pattern recognition,” say, “The hand starts to remember how you move—just like your phone remembers your face over time.”

Instead of “adaptive grip,” say, “If you squeeze something lightly, it grips gently. If you squeeze harder, it tightens more—just like a real hand would.”

This turns tech into something familiar. It helps the patient relax and believe, “Okay, I can do this.”

Explain Feedback as the Hand Talking Back

If your device includes sensory feedback or vibration cues, patients may be unsure what to make of it.

You can say, “When you touch or hold something, the hand gives you a tiny signal—like a whisper. That’s how it tells your brain, ‘I’ve got this.’ It’s the hand’s way of talking back to you.”

This makes the idea feel more like communication than technology. It also gives the patient a reason to pay attention to the sensations, not just the movement.

The more they understand the feedback, the more the brain begins to use it to guide future movements.

That’s how habits form. And that’s how confidence grows.

Guiding the Journey Beyond the Clinic

Remind Patients That Progress Continues at Home

What happens after a fitting session matters just as much—if not more—than what happens during it.

Patients need to know that their best learning happens at home, doing real tasks. You can say, “The hand gets smarter every time you use it. So just putting on your shirt or holding your toothbrush counts as training.”

This takes pressure off formal practice. It also shows that daily life is a key part of rehabilitation.

And when life itself becomes the training ground, the user feels like they’re always improving—no matter where they are.

Be Clear That Setbacks Are Normal

Sometimes users come back after a few days and say, “It was working great before, but now it feels off.” This can scare or frustrate them.

You can reframe this by saying, “That’s actually a good sign. It means your brain and your hand are still learning—and growth can feel bumpy.”

Normalize the ups and downs. Make sure they know that change is part of progress.

This will help them push through tough days instead of giving up too early.

Rebuilding Identity Through the Bionic Experience

Talk About the Hand as a Part of Them

As the brain begins to accept the bionic hand, it starts updating its sense of the body—what scientists call the “body map.” This is where real integration happens.

You can help by referring to the hand in ways that reinforce ownership.

Instead of “the device,” say, “your hand.”

Instead of “the socket,” say, “where your hand connects to your arm.”

These small changes shape how the patient sees themselves.

When the language reflects belonging, the brain follows. And when the brain follows, the bond between user and device gets stronger.

Help Them Reclaim Activities That Define Them

For many users, limb loss meant stepping back from activities they loved—like painting, holding a baby, driving, or playing music.

As they begin to use the bionic hand, these lost actions become powerful milestones.

Ask them, “Is there something you stopped doing that you’d love to try again?” Then use that as a guide for training.

When the hand becomes a way to reconnect with identity, motivation soars. The user isn’t just moving—they’re reclaiming who they are.

That emotional link is what drives long-term use, far more than any instruction manual ever could.

Keeping the Momentum Going

Remind Them Why They Started

There will be moments when users get discouraged. Maybe the progress feels slow. Maybe they compare themselves to others. Maybe they just have a bad day.

During these times, it’s important to gently bring them back to their “why.”

Say something like, “Remember how you told me you wanted to cook again? That’s still happening—step by step.”

By connecting their training to their personal goals, you bring meaning back into the process.

Even a small reminder can rekindle motivation.

Celebrate Progress Out Loud

A patient might not notice how far they’ve come. But you, as the clinician, will.

Make a habit of celebrating small wins openly. Say, “Two weeks ago, you couldn’t hold this object. Now look at you.”

This kind of encouragement builds trust—not just in you, but in their own body and their new hand.

Over time, they’ll begin celebrating themselves, and that self-recognition makes all the difference.

Equipping Patients to Practice Independently

Give Them One Simple Exercise at a Time

Too many instructions can overwhelm. Instead of handing out a long list, focus on one actionable practice they can try at home.

For example: “Today, I want you to hold your toothbrush with your new hand for just one minute—once in the morning and once before bed.”

This is easy to remember, doesn’t feel heavy, and shows quick results.

Once they master that, give the next step. Over time, these short efforts add up to big changes.

Encourage Them to Teach Someone Else

One powerful way to reinforce learning is to ask the user to show a family member or friend how the hand works.

This builds pride. It helps them explain what they’ve learned. And it gives others a chance to encourage them too.

You might say, “Tomorrow, show your partner how you’re gripping things now. Let them see what’s working.”

When others notice progress, it feels more real—and that recognition keeps momentum alive.

Coaching Through Setbacks

Normalize Frustration

When a user hits a wall, it’s tempting for them to assume they’re failing. That’s when they need the most compassion.

Tell them, “Every user—no matter how strong or motivated—goes through tough days. It doesn’t mean you’re going backward. It just means your brain is still figuring things out.”

This gives them permission to struggle without feeling defeated.

It also reminds them that growth is not always visible—but it’s always happening.

Use Gentle Language to Reframe Challenges

Words matter. Instead of saying, “You didn’t complete the task,” try, “Let’s try this a different way.”

Instead of, “You lost control,” say, “Your hand just needs more practice understanding that movement.”

This shifts the focus from blame to curiosity. It encourages the user to stay open, not shut down.

And that openness is what keeps neuroplasticity active and alive.

Connecting Patients to a Bigger Story

Let Them Know They’re Not Alone

Sometimes patients feel like they’re the only one struggling to adapt to a bionic hand. That loneliness can be a quiet barrier.

Remind them that many others are on the same path.

Say, “There are hundreds of people across India going through this too. And like you, they’re learning, growing, and finding their strength.”

If possible, connect them to others who’ve used Robobionics devices successfully.

Hearing another person’s story can often create a breakthrough where instruction alone couldn’t.

Guiding the Patient Into Long-Term Ownership

Make the Hand a Part of Their Story

One of the most important milestones in a user’s journey is when they stop thinking of the bionic hand as something they were given, and start seeing it as something they’ve grown into.

You can encourage that by saying, “You’ve worked hard to build this connection. This hand is part of you now—not because of wires or motors, but because you made it yours.”

That shift in identity—from recipient to owner—is a sign that the brain and the body have truly adapted.

It’s when the user begins to see the hand not as a reminder of loss, but as a symbol of strength.

Help Them Set a Vision for the Future

After rehab ends and the basics are learned, many users ask, “What now?”

This is a great opportunity to co-create a long-term vision.

Ask them, “What’s something you’ve always wanted to do that we haven’t tried yet?” It might be tying shoelaces, writing a note, or even riding a motorbike again.

Whatever their goal, frame it as the next adventure. That sense of forward motion helps keep learning alive.

You’re no longer just supporting recovery—you’re now unlocking possibility.

How Robobionics Supports the Full Journey

Our Technology Learns With You

At Robobionics, we’ve designed every product to respond to the real world—not just to lab conditions.

Our Grippy™ Bionic Hand is lightweight, intuitive, and powered by natural muscle signals. But what truly makes it special is how it adapts.

As users train and explore, the hand continues learning. Movements become smoother. Errors become rarer. And the experience starts to feel natural.

For patients, this means less frustration. For clinicians, it means faster fittings, fewer follow-ups, and happier outcomes.

Sense of Touch™ and Emotional Confidence

Grippy™ also features Sense of Touch™—our patent-pending feedback system that allows users to feel subtle pressure while gripping.

This might seem like a small thing. But to the brain, it’s huge.

That touch builds trust. It gives users real-time confidence. It tells them, “You’ve got this.”

This feedback doesn’t just improve control. It deepens connection. And that connection drives long-term use better than any instruction manual ever could.

Support Beyond the Hand

We also provide a full care ecosystem that includes:

- A Gamified Rehabilitation App to make training enjoyable

- Ongoing check-ins and support tools for clinicians

- Personal training programs tailored to every user’s pace

We don’t just deliver devices. We deliver outcomes.

If you’re a clinician looking to introduce Grippy™ to your patients—or simply want to learn more—you can schedule a free, no-pressure demo here:

https://www.robobionics.in/bookdemo

We’re proud to walk this journey with you.

Final Words: Simple Language, Lifelong Impact

Helping patients understand adaptive bionics isn’t just about explaining wires, sensors, or muscle signals.

It’s about helping them see what’s possible.

It’s about using kind words, clear stories, and small wins to open a door between technology and trust.

You are more than a clinician. You are the guide, the coach, the cheerleader, and sometimes, the only voice reminding a patient that they’re not broken—they’re just learning something new.

And when that learning happens with the right support, incredible things follow.

Together, with tools like Grippy™ and care that listens, we can help people reconnect with themselves—one movement, one gesture, one step at a time.

Thank you for being part of that mission.