A stroke changes everything in an instant. It affects the brain, the body, and often, the way a person moves and feels. In rare but very real cases, stroke survivors may also face limb loss—either due to severe tissue damage, complications from paralysis, or poor circulation.

Losing a limb after a stroke creates unique challenges. Muscle weakness, nerve damage, and brain-muscle disconnect all come together. Rehabilitation becomes complex. Standard therapy routines often need to be rethought from the ground up.

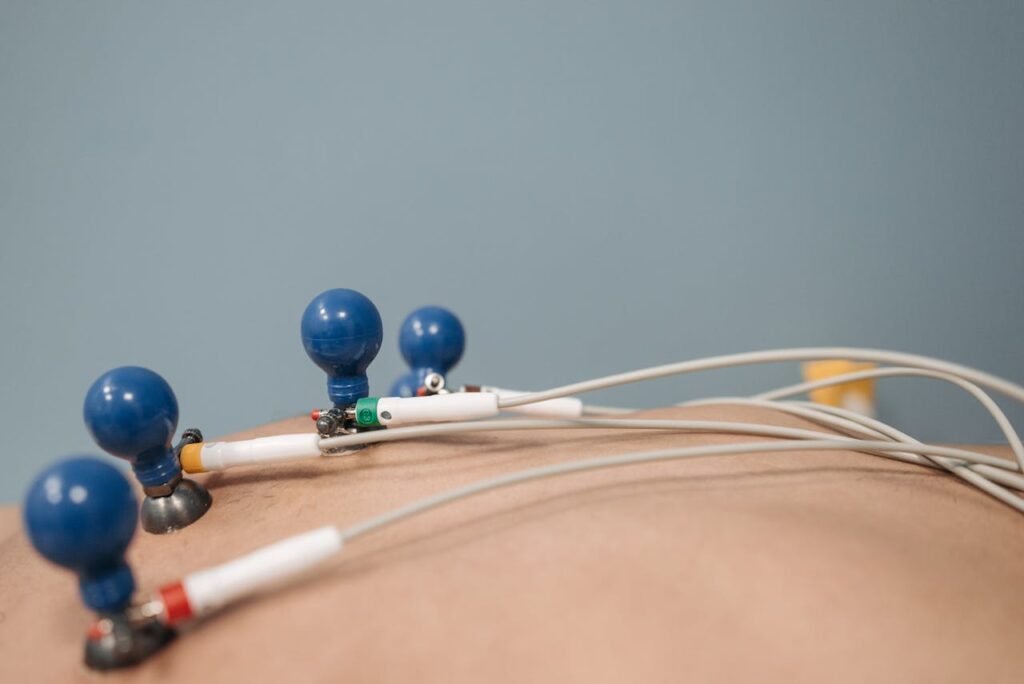

One tool that can support this journey is EMS—Electronic Muscle Stimulation. EMS helps reawaken muscles, rebuild strength, and retrain the brain to connect with the body. But for stroke survivors with limb loss, EMS isn’t one-size-fits-all. It needs to be tailored. Gently. Carefully. Intentionally.

In this article, we’ll explore how EMS can help people who’ve lost a limb due to stroke. You’ll learn how to use it safely, when to start, what strategies work best, and how caregivers and clinics can build routines that truly support recovery.

Let’s begin by understanding how stroke and limb loss combine to affect the body.

Understanding the Unique Challenges

Stroke Changes the Brain-Muscle Connection

A stroke damages parts of the brain that control movement. That makes it harder for the brain to send clear signals to muscles.

When someone loses a limb after a stroke, both the body and the brain need to adapt. It’s not simply about regaining strength. It’s also about helping the brain understand what the body can still do.

EMS steps in to bridge that gap. By creating artificial signals—through gentle pulses—it reminds the brain that muscles still exist and can move.

This reminder helps retrain the brain, allowing it to rebuild connections that were weakened or lost.

Paralysis and Muscle Weakness

Many stroke survivors face partial paralysis or severe muscle weakness in parts of their body—even before limb loss happens.

When a limb is gone, the muscles around the missing limb may shrink further or stop working altogether. This can make prosthetic use difficult or impossible.

EMS helps by keeping the muscles active. Even if movement isn’t voluntary, the pulses keep the muscle tissue healthy, flexible, and engaged.

Over time, as the brain learns to respond again, these muscles may begin to respond to intention—and EMS becomes a bridge to voluntary movement.

Emotional and Physical Layering of Loss

Stroke-induced limb loss affects both body and mind.

The physical trauma of amputation is compounded by the emotional shock of a stroke. Regaining confidence, trust in one’s body, and motivation can be far more complex than after standard amputations.

When adding EMS to therapy, it’s not just about which settings or electrode positions to use. It’s about timing, pacing, and emotional readiness.

Therapy must move at the pace of comfort. The first session may focus more on reassurance than contraction—or on helping the user understand what’s happening inside their body again.

Tailoring EMS for Stroke-Induced Limb Loss

Start with Observation, Not Action

Before applying any EMS device, the first step is understanding the body’s current state.

Stroke survivors may have altered sensation. Some areas may be numb, while others are overly sensitive. The skin may be dry, thin, or prone to bruising. The residual limb may not respond to touch the same way as other parts of the body.

This is why observation is crucial. Spend time gently touching and feeling the stump area. Look for muscle tone, skin color, swelling, or pain response. Ask the person how it feels. Their feedback matters just as much as what the eyes can see.

These observations guide where to place the pads, how strong the pulse should be, and how long the sessions should run.

Keep Settings Gentle and Stable

The brain after a stroke needs calm and predictability. Sudden high-intensity stimulation can feel alarming—not just physically, but neurologically.

Start with very low settings. A small, rhythmic contraction is better than a strong pull. The goal isn’t to see dramatic muscle movement. It’s to offer the brain a familiar signal—something it can recognize and respond to.

Pulse width should stay between 100–200 microseconds. Frequency can start as low as 20 Hz. Session times should be limited to 10–15 minutes in the first week, with close monitoring.

The person should never feel pain, sharpness, or involuntary spasm. If they do, stop and reassess immediately.

Let the user remain in control. Even if the session is cut short, that moment of choice builds trust in the process.

Match Sessions With Brain Relearning

EMS is most effective when used alongside active thinking. This means the person should try to mentally engage the muscle during the pulse.

Even if the limb is missing, this mental focus helps. The brain imagines movement, the EMS gives the physical sensation, and together they form a bridge.

This is called motor imagery, and it’s powerful. When the user thinks “move,” and EMS provides a small contraction at the same time, the brain rewires itself faster.

Therapists can encourage this by asking the person to say the movement out loud. For example: “Now I’m closing my hand,” or “Now I’m lifting my wrist.”

It might seem simple, but pairing thought with stimulation is what helps the brain relearn movement—even when a limb is gone.

Build a Fixed Routine With Flexibility

Stroke survivors often feel overwhelmed by change. A routine brings comfort.

EMS should happen at the same time each day, in the same room, with the same device and setup. This helps the brain recognize the session as a safe, expected experience.

But the routine should also allow flexibility. If the user feels tired, emotional, or unfocused, it’s okay to shorten the session or skip it altogether. Therapy must work with the person’s energy—not against it.

Allow the person to choose music, lighting, or even a favorite scent during EMS. These small comforts increase participation and emotional connection.

If possible, link EMS to another daily habit—after morning tea, before a nap, or during TV time. Familiarity builds trust, and trust builds consistency.

Prioritizing Safety in EMS Use

Skin Checks and Sensory Awareness

Stroke survivors often have reduced feeling in certain parts of their body. They might not notice when something hurts, burns, or rubs the wrong way.

This makes daily skin inspection non-negotiable. Before every EMS session, caregivers or users must gently check the skin. Look for any redness, swelling, scabs, or unusual color. Feel for warmth, dryness, or sensitivity.

Use a mirror if the person can’t see the stump area clearly. Any wound, cut, or bruise should mean skipping EMS for the day. Even a small skin issue can grow quickly if stimulation continues.

After each session, check again. If redness lasts more than 30 minutes, the setting may be too high—or the session too long.

It’s also wise to moisturize dry skin after each session with a simple, non-fragrant cream. This keeps the skin supple and prevents cracking.

Choosing the Right Equipment

Not all EMS devices are the same. For stroke-induced limb loss, the EMS machine should allow for:

- Adjustable intensity and pulse width

- Smaller pediatric or custom-sized pads for delicate skin

- Battery or mains operation depending on safety preference

- Visual indicators or simple buttons for users with limited hand control

Devices should be easy to hold or mount. Large buttons and simple displays help stroke survivors who may have impaired vision or dexterity.

Some clinics provide EMS kits tailored for this group. These kits may include visual pad placement guides, reminders for safety checks, and simple logbooks for tracking progress.

Before starting at home, it’s best to practice under supervision at least 2–3 times in a clinic setting.

The Role of Caregivers in EMS Therapy

Gentle Guidance and Emotional Support

Most stroke survivors who have lost a limb rely on someone for support—either a spouse, family member, nurse, or friend.

Caregivers are essential to EMS success. They help set up the device, apply pads, monitor response, and offer comfort throughout the session.

But their most important role isn’t technical—it’s emotional.

Many stroke survivors carry fear. Fear of pain. Fear of failure. Fear of being a burden. When a caregiver stands beside them with patience and kindness, it reduces that fear.

Let the user feel in control. Ask before adjusting settings. Talk them through each step. Encourage without rushing.

Celebrating small moments—like completing a 10-minute session or feeling a new muscle contraction—makes a huge difference.

Helping With Memory and Routine

Stroke can affect memory, attention, and planning. A caregiver can help by creating gentle reminders for therapy, tracking session times, or preparing the space.

Having a shared notebook helps. Write down each session’s date, duration, intensity, and how it felt. Over time, this becomes a roadmap that guides progress.

Photos can also help with pad placement. Take a picture of the correct electrode positions so that caregivers can refer back to it later.

Even better—record short videos of the therapist demonstrating setup. These visual tools make the home routine more accurate and confident.

EMS as Preparation for Prosthetic Training

Rebuilding Muscle Signals

If a stroke survivor is preparing for a prosthetic—especially a myoelectric one—strong and reliable muscle signals are essential.

But stroke damages more than muscles. It changes how signals travel from brain to limb. EMS helps retrain this pathway.

By stimulating muscles near the stump regularly, EMS improves the clarity of these signals. Over time, this makes it easier for prosthetic sensors to pick up and respond.

It’s not just about strength. It’s about control, timing, and rhythm.

Therapists may recommend doing EMS sessions before putting on a prosthetic—like a warm-up for the nervous system. This primes the body and improves performance.

Reducing Frustration in Early Prosthetic Use

Learning to use a prosthetic is already hard. For stroke survivors, it can be twice as difficult—because the brain is still healing, too.

EMS helps reduce this frustration. It builds familiarity with muscle activation, prepares the body for the prosthetic’s weight and movement, and gives the user a small sense of control.

That small control grows. It becomes confidence. And confidence is the foundation of independence.

Long-Term EMS Strategies for Stroke Survivors

Healing Takes Time, and That’s Okay

Stroke recovery is slow. Limb loss recovery is slow. Together, they form a journey that requires great patience.

There’s no “fast track” when it comes to healing the brain and rebuilding lost strength. But EMS, used steadily and gently over time, supports that journey.

The key to long-term EMS use is consistency. Even short sessions, done regularly, build better results than longer sessions done sporadically.

It’s okay to miss a day. It’s okay to have weeks where the person doesn’t feel ready. What matters is that the person returns to therapy when they can—on their terms, without pressure.

This slow, steady use helps prevent muscle wasting, improves prosthetic fit, and keeps the nervous system active. It gives the brain a reason to keep learning.

Adapting EMS With Life Changes

As the person’s body changes—due to age, other health issues, or prosthetic training—the EMS routine should change too.

What worked three months ago may be too strong or too mild now. That’s why regular reassessment is important. Clinics should schedule EMS reviews every few months, even if the person isn’t visiting weekly.

Changes in medications, nutrition, or emotional state can also affect how EMS feels. Always listen to the body. If something starts feeling wrong, it probably is.

Caregivers and users should keep sharing updates with the therapist. This ensures the therapy stays relevant, safe, and useful as time goes on.

Supporting Emotional Recovery Through EMS

Rebuilding a Sense of Control

Stroke takes away more than strength. It takes away confidence. It changes how people see their body and their ability.

EMS, while technical on the surface, is also a tool for emotional rebuilding.

When a stroke survivor feels a muscle respond for the first time, it can feel like a breakthrough. It proves that part of their body is still alive, still working, still theirs.

Even the simple act of starting an EMS session gives a sense of control—something that many stroke survivors feel they’ve lost.

This sense of control should be protected and encouraged. Don’t rush the person. Let them lead the pace. Celebrate every little milestone, no matter how small it seems.

Making Therapy Personal and Meaningful

Therapy must feel human. It must feel connected to real goals.

If a person wants to use a spoon again, build EMS into hand and wrist activation. If they want to stand or balance better, focus on hip and thigh stimulation.

Make each session meaningful. Tie it to a personal goal or an emotional win.

That goal could be playing with grandchildren, cooking a meal, or typing on a computer again. Keep that goal visible. Remind the user why they’re doing this.

Therapists can also use storytelling. “This muscle we’re working on today helps you hold your cup of tea.” Small explanations make therapy less abstract—and more motivating.

Designing Tailored EMS Programs for Stroke Clinics

One Size Doesn’t Fit All

For stroke survivors with limb loss, standard EMS templates don’t work.

Every person comes with a different stroke history, different brain patterns, and different physical outcomes. Clinics must build EMS programs one person at a time.

Start with a full assessment: motor function, skin condition, sensation level, emotional readiness, and cognitive ability.

Then, create a short EMS plan—just 1 to 2 weeks—with daily or alternate-day use. Reassess early. Adjust slowly. Grow the routine as the user grows.

This approach prevents early burnout or fear and builds confidence through small wins.

Combining EMS With Broader Rehab Tools

EMS should never be used in isolation. It works best when it’s paired with other tools.

Use EMS before or after physiotherapy. Pair it with speech therapy, if the person struggles to communicate. Use it during mirror therapy or with guided imagery.

Some clinics also pair EMS with music or visual cues, which helps the brain build stronger connections during stimulation.

If your clinic serves a large number of stroke survivors, consider building a “Neuro-EMS Starter Kit” with visual guides, caregiver training, and a follow-up support plan. This simplifies home use and improves adherence.

You can also run group sessions for stroke survivors using EMS in a monitored setting. Peer interaction brings comfort, lowers anxiety, and increases commitment.

Real-Life Success With EMS After Stroke and Amputation

Rekindling Movement One Step at a Time

In a clinic in southern India, a 63-year-old man named Raghavan began EMS therapy after a stroke led to partial paralysis and eventual below-knee amputation.

At first, he had very little control over the remaining thigh muscles. His prosthetic sat unused in the corner for months. But with daily EMS sessions—just ten minutes a day—his posture improved. His muscle strength came back slowly. Most importantly, he began trusting his leg again.

By the end of four months, he was walking down his street with a walking stick and a confident smile.

EMS didn’t make that happen alone. But it gave his therapy the boost it needed to work.

There are many stories like his—men and women who thought their muscles were gone, only to feel them stir again after gentle stimulation. These moments matter.

They tell us that recovery, even when delayed, is still possible.

A Son Helps His Mother Rebuild Her Balance

In another case, a young man trained by a rehab therapist began using a home EMS kit to support his 70-year-old mother, who had lost her arm post-stroke.

Together, they followed a simple routine. Every evening, for just 12 minutes, he applied EMS to her upper arm stump and guided her through basic movements. The stimulation didn’t just help with muscle control—it became a bonding ritual.

She reported feeling calmer, stronger, and less frustrated. Eventually, she began trying a light prosthetic. Without EMS, her muscles may have never been strong enough to handle it.

Her son says EMS gave them more than muscle tone. It gave them connection, trust, and hope.

What Families Should Know

Take It One Day at a Time

EMS is not a quick fix. It works best when used slowly, gently, and with care. Some days will go well. Others might feel like a step back.

This is normal.

Support your loved one by showing up—not just to run the device, but to offer quiet encouragement. Let them feel safe. Let them lead.

Even if progress seems small, remember: every pulse is helping. Muscles remember. So does the brain.

Ask for Help When You Need It

Families don’t need to figure everything out alone. Therapists, prosthetists, and EMS device experts can offer tailored guidance, videos, and follow-up support.

If something feels confusing or concerning, pause and reach out.

Robobionics offers free consultations and video demos for families learning how to use EMS after stroke and limb loss. You don’t need to guess your way through it.

Start at your own pace—with people who understand what you’re going through.

Final Thoughts: A Path Forward After Stroke and Amputation

EMS isn’t magic. It doesn’t bring back a limb. It doesn’t undo the damage of a stroke.

But it does offer something deeply valuable: movement, strength, and connection—between the body, the brain, and the person behind it all.

It’s a quiet, steady rhythm of progress. One that supports muscle health, prosthetic training, and personal pride.

At Robobionics, we believe everyone deserves a chance to rebuild—not just physically, but emotionally. Especially those who’ve already survived so much.

If you or someone you care for is recovering from stroke-induced limb loss, let’s talk. Our team can help you begin EMS therapy with care, clarity, and compassion.

Schedule a free consultation at www.robobionics.in/bookdemo

Because every life after stroke still holds strength. And every step forward, no matter how small, deserves support.