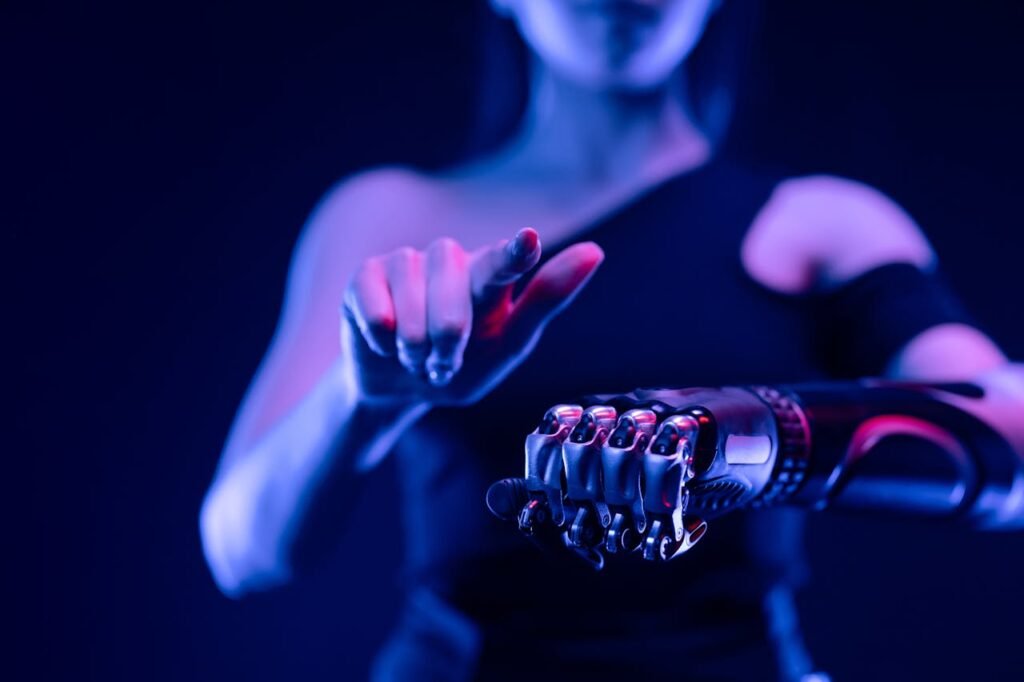

Helping someone learn to use a bionic hand is not just about technology. It’s about the brain.

Even the most advanced prosthetic needs one important thing to work well: a brain that knows how to control it.

When a person loses a hand, their brain doesn’t forget it. The signals are still there. The challenge is teaching the brain how to use those signals with something new—something that isn’t flesh and bone, but metal and sensors.

This process is called neural training. And as a clinician, you play a key role in guiding it.

In this article, we’ll explore how the brain learns to control a bionic device, what you can do to help your patients train effectively, and why emotional support matters just as much as muscle signals.

Let’s begin by understanding what happens in the brain after limb loss—and how that shapes everything that follows.

What Happens in the Brain After Limb Loss

The Brain’s Map Remains

When someone loses a limb, the body changes. But the brain doesn’t forget. Deep inside, there’s still a map—a network of cells that used to send and receive signals from that hand or arm.

This map is still active.

It may not have a limb to control, but the brain still tries. That’s why many patients feel phantom sensations. They might feel itching, tingling, or even pain in a hand that’s no longer there.

These signals may seem like a problem, but they’re actually an opportunity.

They show us that the brain still wants to move the hand. And that’s the starting point for teaching it to move a bionic one.

Neuroplasticity: The Brain’s Power to Adapt

The brain is flexible. It can rewire itself, shift how it works, and build new pathways.

This ability is called neuroplasticity.

In the case of a bionic limb, the brain must learn how to send signals to the device instead of the missing limb. It must adjust how it thinks about movement.

It’s like learning a new skill—riding a bike, playing a piano, or speaking a new language. It takes time. But it’s possible.

And with the right guidance, it can even happen faster than most people expect.

Starting the Neural Training Journey

It Begins Before the Prosthetic Is Worn

Neural training doesn’t begin when the patient puts on their bionic hand. It begins earlier.

Even before fitting, you can start preparing their mind.

Talk to them about their phantom sensations. Explain that their brain is still active, and that’s a good thing. Encourage them to imagine moving their missing hand. Ask them to try tensing their muscles. Let them feel the connection is still there.

These simple exercises build awareness. They remind the brain that movement is still possible.

And when the device is ready, the brain will already be listening.

First Time With the Bionic Hand

When the patient first tries on their bionic hand—whether it’s Grippy™ or another device—don’t rush.

Start with the basics. Ask them to relax. Then ask them to think about opening or closing their hand.

Often, the first attempts will be slow, awkward, or uneven. That’s normal.

The brain is sending signals. The device is responding. But the connection isn’t smooth yet.

This is where your role is critical. You are the translator between the brain and the hand.

Help them understand what they’re doing right. Correct gently. Celebrate every small success.

In those early moments, belief matters just as much as technique.

Simple Tasks, Big Impact

In the first few weeks, stick to very simple tasks.

Ask the patient to grip a soft object. Pick up a plastic cup. Move a spoon from one side of the table to the other.

These are not just physical exercises. They are brain exercises.

Each task teaches the brain what works—and what doesn’t. Each success becomes a memory. The brain starts building patterns.

Over time, these patterns turn into habits. The movement feels less like effort and more like instinct.

That’s the goal of neural training: to make bionic control feel natural.

The Role of the Clinician in Neural Training

Be a Coach, Not Just a Technician

Yes, you’re there to fit the device. But your patient needs more than hardware. They need a coach.

They need someone who understands what their brain is going through. Someone who can guide them, adjust their mindset, and help them feel capable.

The bionic hand is only as effective as the belief behind it.

You don’t need to give long lectures. But use clear, calm language. Talk about what’s happening in their brain. Let them know it’s okay to fail. Let them know progress takes time.

When you give patients that emotional space, their brain opens up to learning faster.

Watch the Smallest Movements

As the patient trains, pay attention to details.

Do they tense their shoulder when trying to grip? Do they hold their breath? Do they pause before every move?

These signs show how their brain is processing the task.

Help them relax. Guide their posture. Break down movements if needed.

The brain loves clarity. When the body is calm and the task is simple, the brain learns faster.

Even a shift in wrist angle or elbow position can change how the brain interprets movement.

Be their eyes when they can’t see what they’re doing wrong.

Encourage Repetition, But Add Variety

Repetition is essential for brain training. But doing the same task over and over without variation can become boring or less effective.

Instead, keep the core motion the same but change the context.

If they’re learning to grip, let them grip different objects. A bottle. A soft ball. A pen.

If they’re practicing release, vary the height or weight of the item.

This keeps the brain alert. It has to adjust each time, which strengthens learning.

Variety also makes training more interesting—and patients more likely to continue.

Reinforcing Brain Control Outside the Clinic

Daily Life as a Training Ground

The brain doesn’t only learn during therapy sessions. It learns all the time. In fact, some of the most powerful progress happens outside the clinic—during daily tasks. Picking up a toothbrush, flipping a light switch, opening a drawer—each action reinforces the brain’s control over the prosthetic.

That’s why it’s important to help patients see everyday life as part of their rehab. When they cook, clean, or dress using their bionic hand, they’re not just getting chores done—they’re building new brain pathways. These real-world situations bring meaning to the movement, which encourages the brain to adapt faster.

Encourage patients to try one new task each day with their prosthetic. It could be as simple as holding a book or pouring a glass of water. Over time, these moments stack up and create lasting change in the brain.

Creating Mini Habits for Long-Term Learning

Long training sessions can feel overwhelming. But short, frequent practice can be just as effective—especially when it becomes a habit. Help your patients build a simple routine they can follow at home. It could be five minutes in the morning, five at night.

Even small movements, done mindfully, can strengthen the brain-device connection. Let them pick exercises they enjoy or feel proud of. When patients feel ownership of their practice, they’re more likely to stick with it—and their brain gets more consistent stimulation.

Reinforce that it’s not about perfection. It’s about showing up every day and giving the brain a reason to keep learning.

Emotional Wins Matter as Much as Physical Ones

Progress with a bionic hand isn’t just measured by how well someone grips an object. It’s also felt in how they carry themselves. Regaining movement can lead to regaining confidence, independence, and dignity. These emotional wins matter deeply.

Many users may not notice their own growth until you point it out. As their clinician, you can remind them how far they’ve come. What felt impossible two weeks ago may now feel easy. Highlighting these changes can help the brain feel more connected and the person feel more hopeful.

This emotional encouragement also improves brain learning. A motivated brain is a more flexible, active brain. Belief and effort work together to form stronger neural links.

When Things Get Stuck: Supporting Slow Progress

Recognizing Common Roadblocks

Not every patient will improve at the same pace. Some may take longer to control their bionic hand. Others may lose motivation after an early burst of progress. It’s important to recognize these plateaus and help patients move past them.

Sometimes, the issue isn’t the brain—it’s fatigue, poor posture, sensor misalignment, or even emotional stress. Ask questions. Observe closely. A small tweak in fit, routine, or mindset can restart progress.

Let your patients know that slow progress doesn’t mean failure. The brain learns in waves. A quiet phase doesn’t mean nothing’s happening. Often, it’s the pause before the next leap forward.

Restarting the Brain-Device Conversation

When training seems stuck, go back to basics. Reintroduce simple tasks. Give the brain a clear target. For example, instead of asking them to pick up a pen and move it, ask them to just open and close the hand gently.

These smaller actions remind the brain what success feels like. It helps re-establish the connection that may have weakened from stress or fatigue.

You can also encourage them to change the environment. Sometimes practicing in a different room or with different lighting can spark new engagement from the brain.

Don’t be afraid to take a step back if it helps them take two steps forward.

Bringing in the Support Circle

Family members and caregivers play a key role in neural learning. They can help reinforce practice, celebrate progress, and create a supportive environment. But they need guidance too.

Help the support circle understand what’s happening in the brain. Explain how encouragement—not pressure—helps more. Show them how to assist during tasks without taking over. Let them know that their role is not to fix, but to support.

A calm, patient home environment helps the brain feel safe. And safety is what unlocks learning.

Tools and Techniques to Deepen Brain Engagement

Using Sensory Feedback to Strengthen Brain Responses

One of the most important parts of learning to use a bionic hand is feedback. When the user feels something in return—like a vibration, a buzz, or a change in pressure—the brain starts paying more attention.

This is why Grippy™ includes our Sense of Touch™ technology. It lets the user feel when they’re gripping something. That feeling is what makes the brain say, “I did it.” Without that feedback, it’s like talking into a microphone without hearing your voice. The brain needs that loop to learn better and faster.

As a clinician, help patients notice these sensations. Ask them what they feel when they grip an object. Encourage them to pause, reflect, and remember how it felt. That reflection process strengthens the brain’s ability to recall and repeat successful movements.

Visual Cues and Mirror Work

Another useful tool is visual feedback. Sometimes, watching the movement of their bionic hand helps the brain learn faster. The brain sees the action, matches it with the effort, and stores that pattern.

You can use a mirror during training sessions. Ask the user to move their natural hand while watching its reflection, then try to mirror the same movement with their prosthetic. This activates what are called “mirror neurons” in the brain—cells that help copy and reinforce action.

This technique is especially helpful for users who struggle with coordination or timing. Seeing success visually makes it easier to repeat it physically.

Video recordings can also help. Encourage users to film themselves performing a simple task and watch it later. Seeing their progress builds confidence, which strengthens neural learning.

Tracking Progress to Reinforce Learning

The brain likes proof. When users can see that they’re improving, they feel more motivated—and motivation feeds learning.

As a clinician, try to document their journey. Record what tasks they can do in week one, then again in week three, and so on. Even if the changes seem small, they matter.

This can be done through short notes, photos, or video clips. At key points, show them how far they’ve come. Remind them what they used to struggle with, and what they can now do with ease.

This kind of positive reinforcement doesn’t just boost emotion. It helps the brain lock in those successful patterns. It says: “This works. Let’s keep going.”

Expanding the Range of Brain-Controlled Tasks

Moving Beyond the Basics

Once the patient is comfortable with simple tasks, it’s time to explore more complex actions. These don’t need to be difficult. They just need to involve more coordination, timing, or multiple steps.

For example, instead of just lifting a spoon, ask them to scoop something with it. Instead of picking up a cup, have them carry it across a room. These extra layers challenge the brain to control the hand more precisely.

These tasks help the brain form more refined pathways. They also make the prosthetic feel more natural—less like a tool, more like a true part of the body.

Encourage the user to think about what they want to do in their daily life. Whether it’s cooking, writing, or even gardening, use those real-life goals to shape training.

Introducing Two-Handed Coordination

Many users are focused on learning how to use the prosthetic hand alone. But in real life, most tasks require both hands. Training them to work together opens up a new level of control.

Ask the user to try folding a towel, opening a container, or tying their shoelaces—any activity that requires cooperation between both arms. This encourages the brain to treat the prosthetic as part of the whole body, not just a separate tool.

It also improves balance, movement flow, and task planning. The brain becomes more engaged when multiple parts of the body are involved.

As always, start small and go slowly. Let the user lead the pace. Their comfort builds better results.

Practicing in New Environments

Doing the same task in the same room can become routine. But the brain learns better when it’s slightly challenged. That’s why changing the environment can help deepen neural training.

Ask your patients to try simple exercises in a different room or position. If they always practice sitting at a table, ask them to try while standing or walking. If they’ve only used their hand in the clinic, ask them to try something in their kitchen or living room.

The new surroundings force the brain to adjust. This makes the movement patterns more flexible and reliable. It also builds real-world confidence—something every user needs.

The Emotional Heart of Neural Training

Rebuilding More Than Movement

Helping someone train their brain to use a bionic device isn’t just about movement. It’s about rebuilding a sense of control, confidence, and identity. When patients succeed with their prosthetic, they’re not just able to hold objects—they’re able to hold on to life again.

For many users, the emotional impact of regaining movement can be overwhelming. It marks a shift from helplessness to independence. They feel capable, valued, and seen. That emotional response is as much a part of the brain’s learning as the grip itself.

As a clinician, being part of that journey is a privilege. You’re not just fixing or fitting. You’re helping someone rediscover their strength.

Creating a Safe Space to Try, Fail, and Grow

Failure is part of neural learning. Every mistake teaches the brain what to do differently next time. But for the user, especially early on, those failures can feel discouraging.

That’s why your tone, patience, and encouragement matter so much.

If a user drops something, reframe it as a step forward. If they forget a movement, remind them that the brain is still building. If they feel frustrated, remind them how far they’ve come.

This emotional safety makes the brain more receptive to learning. It gives your patient the courage to keep going, even when it’s hard.

You don’t need to say much. Sometimes, a nod, a smile, or a calm “Let’s try again” is all it takes.

Small Wins Lead to Big Change

One of the most important messages you can share with your patients is this: every small win matters.

Gripping a toothbrush. Holding a cup without dropping it. Lifting a light bag. These moments may seem minor—but in the brain, they are huge.

Each success is a signal. It tells the brain, “This works.” That signal is reinforced through repetition, feedback, and trust. Over time, small wins stack up into lasting control.

By helping your patients notice these wins, you help their brains believe in progress. You help their minds catch up to what their bodies are learning.

The Future Is Brain-Driven, and You’re Leading It

Smarter Devices, Smarter Training

At Robobionics, we’re building prosthetic hands that respond to the brain in more natural ways. With technology like myoelectric sensors and Sense of Touch™, we help users feel more connected—and more in control.

But no matter how advanced the device, it still needs a guide. Someone to translate tech into trust. Someone to teach the brain how to adapt.

That guide is you.

As a clinician, you’re not just part of the process—you are the key to it. The way you talk, listen, and lead has a direct impact on how the brain forms its new patterns.

As tech continues to evolve, your role becomes even more valuable.

Lifelong Learning and Support

The brain never stops learning—and neither should we. Each user teaches us something new. Each success story helps shape better care for the next one.

Stay curious. Try new training approaches. Share your insights with other professionals. Attend workshops, speak with device manufacturers, and ask questions about how to improve outcomes.

You are part of a growing movement that puts brain science at the heart of prosthetic care.

If you’d like to learn more about Robobionics’ approach to neural integration and see our bionic hand in action, we’d love to hear from you.

Final Words: Healing Hands Begin in the Brain

Helping patients train their brain to control a bionic device is about more than science or mechanics. It’s about belief, patience, and the power of second chances.

You are giving someone the tools to move again—but also to live again. And with every patient you help, you’re also changing what’s possible.

We believe in a future where prosthetics don’t feel like machines, but like natural extensions of the self. Where users don’t just adapt—they thrive. And where clinicians are celebrated as the real bridge between technology and humanity.

Thank you for doing this work. Thank you for helping people feel whole again—one brain, one hand, one step at a time.

To explore more, or to book a demo with our team, visit:

https://www.robobionics.in/bookdemo

Let’s keep building a world where every hand—real or bionic—reaches its full potential.